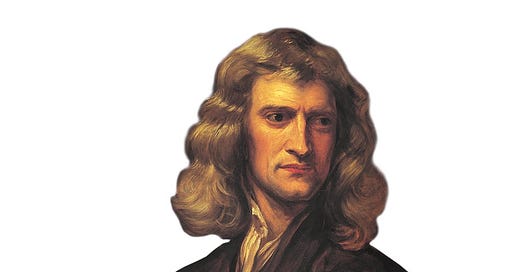

The World's Greatest Scientist. . . and Bibliomancer

Everything you think you know about Sir Isaac Newton is wrong...

We have no room for the mystical in science.

.Adam Rutherford, A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived.1

The biblical Book of Daniel is a book of prophecy. It contains, purportedly, the recorded word of the god of the slain son auguring a future horrible and resplendent. The words of the Book form stories, these stories contain dreams, these dreams contain messages, these messages contain divine import intended for the benefit of humankind—so say the congregants devoted to their god’s chosen prophet, Daniel.

One of these portentous reveries can be found in the fifth of the chapters of Daniel:

King Belshazzar gave a great banquet for a thousand of his nobles and drank wine with them. As they drank the wine, they praised the gods of gold and silver, the gods of bronze and iron, and the gods of wood and stone. In the same hour abruptly came forth the disembodied fingers of a human hand that commenced inscrivening on the plaster of the royal palace wall. The king studied the hand as it wrote its message and his face turned pale and the joints of his loins weakened and his knees smote one against the other. This is the inscription written by the ghostly hand upon the king’s wall: MENE, MENE, TEKEL, PARSIN.

The faithful believe this was not merely a historical, if supernatural, edict for King Belshazzar, but a divine message for all humankind regarding our final destination.

For the faithful, the Book of Daniel is not merely a roadmap for understanding the god of the slain son’s intended plan for reality, it is a revelation about the nature of time itself. To discern and interpret the holy premonitions concealed within the book’s intricate text does not require faith alone, contend the believers, but too intelligence, wisdom, and assiduous dedication.

One man believed that he alone amongst his peers had attained the hard-earned competence in prophetic interpretation necessary to extract liveborn the mysteries of time and fate cloaked within the Book of Daniel.

Not coincidentally, that hierophant and master of occult time lore was the most celebrated scientist the world has ever known: Sir Isaac Newton.

.2

“The Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica by Isaac Newton, first published in Latin in 1687, is probably the most important single work ever published in the physical sciences,” rhapsodized Steven Hawking. The Newton of modern physics’ myth is a man of courageous reason and unrelenting logic, a man who unshackled humankind from the stultifying chains of superstition and liberated the rational mind to take flight, soaring into three hundred years of scientific exultation.

This Newton is false. A Disneyfied character for children who need to learn that every action inaugurates a counteraction through a clean and perfect symmetry of momentum. A vision of the scientist shaped out of the propaganda of logic: science is a safe, secular activity, conducted by citizens with an eye on the sun.

If Newton was resurrected from his golden coffin and set before a congregation of twenty-first century physicists, he would surely denounce them as blasphemous and soulless. Newton would despise their overweening atheism and their embrace of the pure abstract theology of reductionism for the simple reason that Newton’s core conviction—his core identity as a human seeker—was that it is possible to dig god’s intentions out of the dark loam of holy writ, not in some abstract, mathematical fashion, but in a technicolor eruption of mystic revelation.

Newton was convinced that “the holy Prophecies” of scripture were nothing less than the “histories of things to come.” He believed that God was not bound by time as are humans, allowing him to see the “end from the beginning.” At the same time, biblical prophecy is written in highly symbolic language that demands finely honed skills of interpretation—skills that Newton spent a lifetime mastering and which he eagerly applied to the Book of Daniel.

Newton was no Apollonian champion. No humanistic hero lifting mankind from the shadows of superstition. Newton was a remorseless, self-absorbed insurgent willing to violate all human laws and norms in his private pursuit of prophetic revelation. Newton believed that Christianity in general, and the Anglican church in particular, had been corrupted from within. Fortunately, he alone was able to retrieve the unremembered holy truths that humankind once reveled in.

Indeed, Newton’s Principia Mathematica, the origin story of scientific physics, was considered by its author not to be the original, groundbreaking product of his personal diligence and ingenuity, but rather, the recreation of lost knowledge once held by the ancients, who knew directly and untainted the true prophecy of the god of the slain son. A god who Newton lovingly referred to as Ancient of Days.

In a set of notes known as the “Classical Scholia,” Newton argued that key doctrines of the Principia, such as the earthshaking claim that the force of gravity was universal, were hidden within philosophical doctrines whose true import the ancients concealed from the vulgar masses using poetic allegories. (For the second edition of Principia, Newton intended to include passages from Pythagoras’ discussion of the music of the spheres where Newton believed the canny old mystic had camouflaged his knowledge of the inverse square law of gravitational attraction.) Think about this striking irony: the progenitor of modern science, the first person to employ the effective and rigorous application of abstract reason to know the secret mechanics of reality, was diligently hunting for evidence that his achievement was a conspiracy theory.

The Newton of schoolbooks—a scientist’s scientist, battling the quaint superstitions of religion, rejecting obfuscation and mysticism—is a bald-faced fraud. If the real Newton ever encountered this dull and deracinated effigy of the Enlightenment, Newton would have reviled him. For Principia was trivial compared to the ultimate prize chased by Newton:

Correctly interpreting the secret prophecies Ancient of Days implanted within the Book of Daniel.

.3

Only those closest to Isaac Newton knew the truth: that he was always on the verge of being excommunicated, exiled, or thrown in prison. Not because he claimed heretic knowledge of the heavenly spheres. Because he denied the authority of the Anglican church in favor of his own personal blasphemy.

Newton believed the original religion of Christianity, cultivated by the intellectual descendants of Noah, was “the most rational of all others till the nations corrupted it.” In this original, unpolluted belief system, according to Newton, the universe was the temple of God and the ancients integrated their deep, loving knowledge of nature into religious worship. Newton contended these ancient priests “were above other men, well skilled in the knowledge of the true frame of Nature & accounted it a great part of their Theology.”

In Newton’s view, all the major accoutrements of Roman Catholicism and Anglicism were idolatry and superstition, including the doctrine of Transubstantiation; the worship of relics and saints, especially the Virgin Mary; and most heretical of all, the doctrine of the Trinity. Newton despised the celebration of Christ, a mere mortal in Newton’s eyes. Newton used mathematical arguments to contend that God was infinitely superior to the Son, but graciously granted him the temporary and limited use of various divine powers by effecting a union of their wills.

Newton believed myriad false notions were imposed on the public by wayward monks and priests and committees of priests, all of whom worked selfishly to bury the great truths as Newton saw them: that understanding Nature and interpreting prophecy were the interlaced royal roads to divine grace. Indeed, what Newton was seeking in the prophecies of Daniel was insider information on the foretold Apocalypse, the day when all the old Prophets and all the old unsullied religions would re-emerge from their millennial slumber to establish heaven on Earth.

In public, Newton wore a mask of convention to hide his divergent beliefs. It is worth bearing in mind that over the course of his six-decades-long professional life as an esteemed academic, Newton was required to publicly worship in the Anglican Church and frequently swear public oaths to its theological doctrines. Thus, his secret religious writings were exceedingly dangerous: scientists of his generation were often dismissed for heretical views, especially concerning the interpretation of infinity.

In 1694, the physicist Edmond Halley, eponymous with the famous comet he charted, tried and failed to obtain an astronomy position at Oxford. The ecclesiastical authorities denied his application because they found Halley “guilty of asserting the eternity of the world.” In 1710, the physicist William Whiston, who succeeded his mentor Newton as the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge, was expelled from university because he rejected the notion that torment in hellfire was eternal. Surely the punishment for Newton, who dismissed priests and pastors and the divine nature of Jesus and Mother Mary, who asserted that the church was depraved beyond repair—who defiantly claimed that Newton himself was more qualified than the church to interpret its own sacramental texts—would have faced a castigation more harrowing than mere expulsion from university.

The small circle of scientists privy to Newton’s renegade beliefs, like William Whiston, tended to revere both Principia and Newton’s rogue theological work. Whiston recorded that Newton was no theological dilettante, but attained mastery of the primary historical materials relating to the first few centuries of Christianity. Another member of Newton’s inner circle was an Enlightenment hero falsely held up as a spotless beacon of sunny rationalism: the philosopher John Locke, whose ideas influenced the framing of the United States Constitution. Locke quietly joined Newton in the contemplation of god’s recondite omens. Among Locke’s papers was found a remarkable chart composed by Newton. This clandestine document details the timeline of the historic and future unfolding of the apocalypse, worked out by Newton through his analysis of prophetic texts.

How did Newton puzzle out the plan of Ancient of Days—and how did he discern the appointed date of Armageddon?

Using the same methodology he used to fashion Principia Mathematica: the relentless digestion of massive quantities of facts—more than anyone else attempted (and a defining quality of the dark gift)—followed by rigorous mathematical testing guided by ruthless rationalism. After assiduously applying this two-pronged method to the dynamics of matter, Newton became the greatest mathematician on Earth. And after applying the same method with equal diligence to Christian texts, he became the greatest hierophant on Earth.

For Newton, his supreme opus was not Principia (1687), but Observations upon the Prophecies of Daniel (published posthumously in 1733). Newton is most famous for achieving the first great integration in the history of physics, uniting the dynamics of heaven and the dynamics of Earth within a common mathematical framework that physicists refer to as classical mechanics. But to his own mind, Newton had achieved an even mightier integration: demonstrating that the Book of Daniel and the Book of Revelations were not distinct segments of the Christian bible, but a single united prophecy from Ancient of Days revealing the truth about nature and time.

.4

Newton believed that the greatest discovery arising from his infidel bibliomancy was the “beast with ten horns” in the seventh chapter of Daniel. According to Newton, each horn represented a key event or institution in the history of Christianity, and his Observations is filled with dogged analyses of multifarious horns:

It was a horn of the fourth Beast, and rooted up three of his first horns; and therefore we are to look for it among the nations of the Latin Empire, after the rise of the ten horns. But it was a kingdom of a different kind from the other ten kingdoms, having a life or soul peculiar to itself, with eyes and a mouth. By its eyes it was a Seer; and by its mouth speaking great things and changing times and laws, it was a Prophet as well as a King. And such a Seer, a Prophet and a King, is the Church of Rome.

In such mantic and irrational pursuits did Newton while his days.

.5

One special mathematical project consumed Newton until the last of his days: Ancient of Day’s appointed End of Days. Newton believed the god of the slain son had set a specific date for Armageddon. Not an act of violence annihilating the Earth, but a glorious replacement of the old world with a new one heralding an era of beatific peace. We find several documents in Newton’s crabbed hand thronged with calculations and chains of reasoning attempting to ferret out arcane dates that occasionally surpass in their Byzantine complexity the math in Principia:

Whether Daniel used the Chaldaick or Jewish year, is not very material; the difference being but six hours in a year, and 4 months in 480 years. But I take his months to be Jewish: first, because Daniel was a Jew, and the Jews even by the names of the Chaldean months understood the months of their own year: secondly, because this Prophecy is grounded on Jeremiah's concerning the 70 years captivity, and therefore must be understood of the same sort of years with the seventy; and those are Jewish, since that Prophecy was given in Judea before the captivity: and lastly, because Daniel reckons by weeks of years, which is a way of reckoning peculiar to the Jewish years. For as their days ran by sevens, and the last day of every seven was a sabbath; so their years ran by sevens, and the last year of every seven was a sabbatical year, and seven such weeks of years made a Jubilee.

Revealingly, we find Newton at war with himself over whether he is worthy of deducing god’s secret number (the date of Armageddon) or whether the pursuit of such occult knowledge was an unforgivable act of hubris. But eventually he overcame his doubts and performed the forbidden computations and snatched Ancient of Days’ holy number from His intercessional texts: Newton determined the world would end in 2060 AD. Or maybe 2034.

Newton cultivated an unshakeable faith in the notion of absolute time, time standing apart from matter, time fixed and unyielding—a silly and petulant notion snapped apart like a child’s cheap plastic toy by Einstein’s muscular imagination. Modern physicists often cast Newton’s convictions about time as grounded in some particular notion of the dynamics of matter, but the truth was far simpler: Newton bequeathed to three human centuries a science of absolute time because he believed such physics was necessary for the universe to permit prophecy and apocalypse-on-a-deadline.

“The analogy of the clockwork universe so often applied to Newton in popular science publications, some of them even written by scientists and scholars, turns out to be wholly unfitting for his biblically informed cosmology.”1

.6

Isaac Newton’s obsessive attempts at unshrouding the immanent will of his One True God2 justifies my reclamation of Newton for mindscience. Newton is my brother of the living darkness, my brother in alchemy and bibliomancy and divine communion. I embrace my hero and accept him as he is, not as physics wishes him to be: no insecurity or shame compels me to prevaricate about his life and achievements to make him glow with golden rays. I take Newton as Newton chose to define himself, sneering and wild-eyed, crouched asquat omen-larded religion and glassily-abstract science, convinced that he alone disinterred the great secrets of time and purpose.

Newton didn’t stand against religion: he stood against modern physics. It is a sanitized Newton who populates the imaginations of twenty-first physical scientists, a man bravely defying dogma, magic, and credulous thinking. Such a man never was and never could be, for how could one throw oneself into the obliviating fire without believing there will be a hand to lift you from the flames and if you are not willing to hurl yourself off the rooftops of convention than what hope have you of seeing into the furthest reaches where the ultimate truth is to be found?

Snobelen, S. D. (2015). Cosmos and apocalypse. The New Atlantis, 76-94.

Newton even suggested that the physical universe was the divine analogue of the part of the brain (the “Sensorium”) that allowed humans to think and to be aware of the outside world, with the difference that God perceived things “by their immediate presence to himself,” without the mediation of sense organs, nerves, and brain.