How Autism is Made 15: The Tragically Inept History of Autism Science and Medicine

Why can't scientists and psychiatrists give us clear answers about the nature and treatment of the dark gift? Here's the frustrating, amusing, and wholly true story.

.1

This may be the most useful and illuminating article you’ll ever read about the state of autism science, medicine, and treatment in the 2020s. In our super-high-tech Digital Age blessed with such marvels as quantum computers, gravity wave detection, and generative AI, you will come face to face with the shocking reality that autism research and diagnosis remains stuck in nineteenth century methods for understanding the brain.

We will recount the tragic history of humankind’s attempts at fathoming autism and see how, step by inept step, the mainstream diagnosis of autism descended into the dark and lonely swamp of ignorance it remains mired in today.

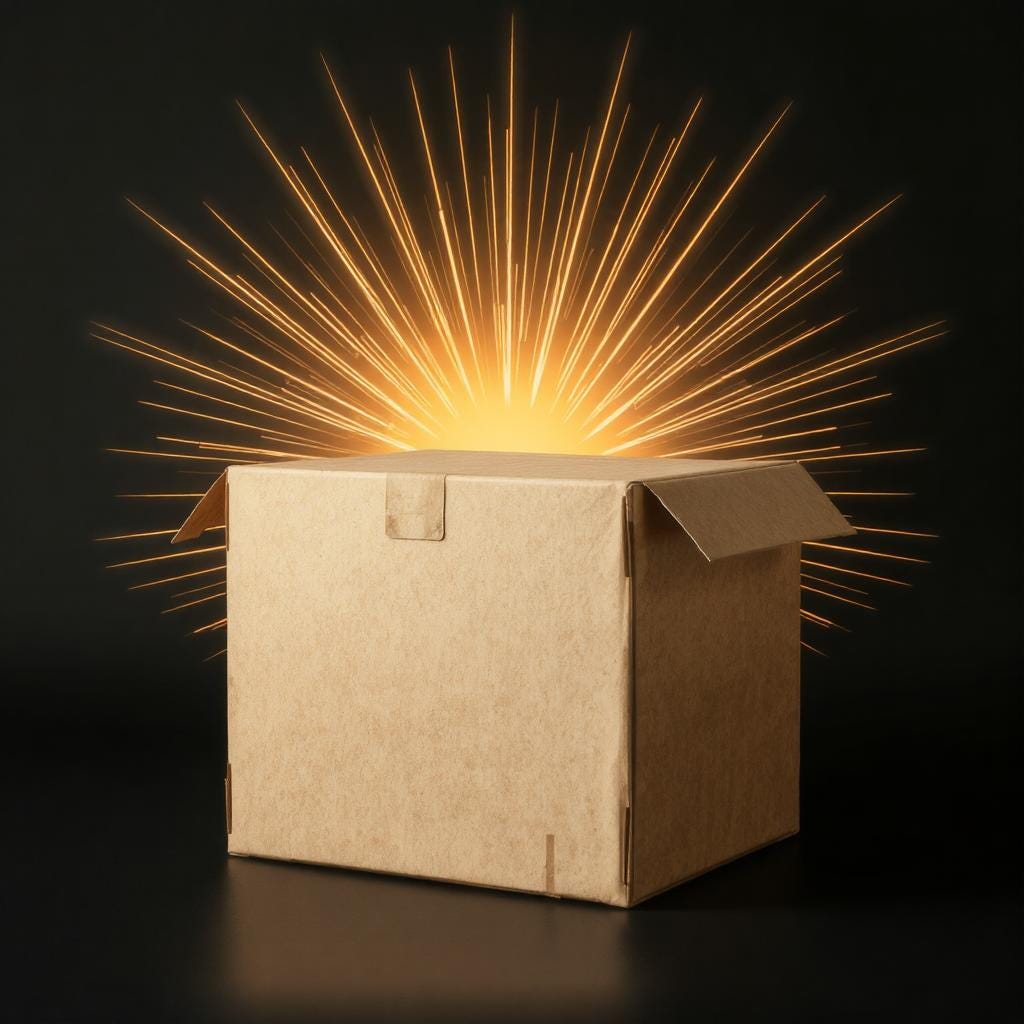

In order to fully appreciate this history we will employ a simple metaphor. The metaphor of the box and the merchandise inside.

Consider the Amazon.com box, delivered to your front door and containing within its cardboard walls glorious shining merchandise.

In our metaphor, each box is a human.

The merchandise inside is a brain. Just as there is a tremendous variety of merchandise in Amazon delivery boxes, there’s a tremendous variety of brains inside humans.

In the 113 years since scientists began studying autism, there have been two methods for investigating the dark gift.

Method #1: examine the box.

The Box-Examiners devote themselves to scrutinizing and documenting all the visibly observable details of the boxes that arrive upon their doorstep. They measure the height of the boxes. Their width. Their length. They examine the packing tape wrapped around the boxes. They weigh the boxes. They shake the boxes and listen for noises. They might put their nose to the box and inhale its scent.

Then comes the hard part. The guessing game. Upon the conclusion of measuring and testing a collection of similar-looking boxes, the Box-Examiners employ their personal intuition to speculate what may lie inside.

What’s in this box? A hairbrush? Needlenose pliers? An oven mitt? Pajamas? Perfume? Maybe one of each?

Method #2: open the box.

The Box-Openers tear off the tape, pry open the flaps, and take hold of the glorious merchandise inside. A Box-Opener actually sees what lies within the box.

Look at this! Who would’ve guessed? A polka-dotted pumpkin!

The history of autism science and medicine is easy to summarize. For a century and a decade, 99% of autism researchers and clinicians have been Box-Examiners. They still reign supreme today.

The Box-Openers are unknown and mostly ignored.

Let’s review the sad and fruitless yet amusing history of autism researchers prioritizing behavioral observation over biology and math. And then, at the conclusion of our chronicle, we’ll open the box and see what’s inside.

.2

Our story commences in 1911. The year the word “autism” entered human vocabulary. A time when there was no math in mindscience. No biology. There was only observation of folks’ behavior.

Only the examination of boxes. Nobody had the faintest clue what merchandise might be hiding inside.

At the time, the World Champion Box-Examiner was Sigmund Freud. The most famous and influential and destructive of all mindscientists. Freud’s approach to studying brains dominated the twentieth century and remains authoritative in the twenty-first, so let’s take a quick moment to investigate how the Godfather of Box-Examining made the crucial jump from examining boxes to guessing what lies inside.

But first, let’s prime your intuition. This will help you understand for yourself what’s really going on with autism diagnosis. Imagine one hundred Amazon boxes are delivered to your door. Further, imagine you’ve never ordered anything from Amazon before and have no idea what’s available to purchase. (The hundred boxes were delivered to your door by accident!)

Do you think there’s any way to figure out what’s inside the boxes without looking inside? Each box might contain the exact same merchandise, or there might be one hundred different kinds of merchandise in them. Or anything in between. Perhaps the boxes come in different shapes and sizes. It seems reasonable to guess that larger boxes contain larger merchandise, and smaller boxes contain smaller merchandise. But if you haven’t seen inside any of the boxes, how can you really know? (If you order merchandise from Amazon, you know that sometimes you find small merchandise inside large boxes.)

The fundamental and insurmountable problem of examining boxes is that until you’ve obtained any concrete information about what’s inside a box or what could be inside a box (maybe because you found a catalog of the merchandise delivered in boxes), any guess about what might be inside—a dog leash? deoderant? dumbbells? donuts? a dancing dinosaur?—is pure, unbridled speculation.

Not science.

Starting in the 1890s, Freud listened attentively as folks reclining on his sofa confessed to him their desires, fantasies, and behaviors. After carefully considering all these verbal details—these observable symptoms—he used his personal intuition to form conjectures regarding what kind of hidden brain structures might produce such symptoms. What he guessed lay inside the box was this: a trio of glorious merchandise. A greedy id, a moralistic superego, and the feeling, thinking ego.

Though I was taught the conjectured neural structures of id, ego, and superego when I was an undergraduate in the 1990s, today the number of neuroscientists who believe in their physical existence is zero. Freud’s trio of hypothetical brain structures simply doesn’t exist. Scientists have opened the box and found no id, ego, or superego lurking inside. Freud did his best to guess what lay inside human skulls, but without any math or biology at all, he failed to translate his painstaking behavioral observations into a single correct conjecture about how brains actually work.

That’s why Freud is nowhere to be found in contemporary neuroscience and is today widely considered a pseudo-scientist, though I find that a bit unfair, considering most clinical psychologists still employ his same nineteenth-century methods today.

Especially his method of guessing, without any physical evidence, what’s inside the brain.

In 1911, working at the same time as Freud, another Master Box-Examiner was concerned with distinguishing boxes that might contain mental illness from boxes that did not. His name was Eugen Bleuler, a Swiss psychiatrist. Bleuler assembled lists of behavioral observations that he believed indicated the presence of mentally ill brains. He was particularly interested in identifying observable behaviors that might be associated with psychotic brains.

Once Bleuler established a list of such behaviors, he coined a new word to describe the hypothetical merchandise he suspected lay inside: schizophrenia. According to Bleuler, some of the key symptoms indicating the presence of schizophrenia included:

Echolalia: the habit of repeating back what someone says, sometimes in a sing-song voice.

Delusions of reference: the professed belief that external events have special or supernaturally relevant personal meaning.

Autism: Bleuler coined another new word, derived from the Greek auto meaning self, to describe what he perceived as a key symptom of schizophrenia: “the inclination to divorce oneself from reality.”

Autism, as proposed by Bleuler, was never intended to be a standalone mental illness. He didn’t think autism was inside the box. He thought autism was a box measurement: an observable form of behavior (an inclination to divorce oneself from reality) that indicated the presence of a psychotic brain.

Bleuer first described “schizophrenics” exhibiting the symptom of “autism” in his 1911 book Dementia Praecox, humankind’s very first account of the dark gift:

They sit around with faces constantly averted, looking at a blank wall; or they shut off their sensory portals by drawing a skirt or bed clothes over their heads. Indeed, formerly, when the patients were mostly abandoned to their own devices, they could often be found in bent-over, squatting positions, an indication that they were trying to restrict as much as possible of the sensory surface area of their skin. . .

In the same way as autistic feeling is detached from reality, autistic thinking obeys its own special laws. To be sure, autistic thinking makes use of the customary logical connections insofar as they are suitable but it is in no way bound to such logical laws. Autistic thinking is directed by affective needs; the patient thinks in symbols, in analogies, in fragmentary concepts, in accidental connections. Should the same patient turn back to reality he may be able to think sharply and logically. Thus we have to distinguish between realistic and autistic thinking which exist side by side in the same patient. In realistic thinking the patient orients himself quite well in time and space. He adjusts his actions to reality insofar as they appear normal. The autistic thinking is the source of the delusions, of the crude offenses against logic and propriety, and all the other pathological symptoms. The two forms of thought are often fairly well separated so that the patient is able at times to think completely autistically and at other times completely normally.

Let’s be crystal clear about what’s going on here, because this will be the same story all the way through into the twenty-first century. Bleuler made detailed, thoughtful observations of the behaviors of humans in his care and pointed out that certain collections of behaviors consistently appeared together in a subset of humans. (Like a set of boxes with similar sizes and weights.) He speculated that this collection of symptoms indicated that “schizophrenia” lay inside the brains of these individuals. But Bleuler possessed zero insight, zero biology, zero math regarding how the neural dynamics of these “schizophrenic” humans (or any humans, for that matter) might actually operate.

Bleuler was a first-rate Box-Examiner: nobody is questioning the honesty or accuracy of his box observations. He measured, weighed, and sniffed each box with admirable attentiveness.

But as with Freud, there was no scientific basis whatsoever for making the leap from examining boxes to knowing what might lie inside. (A hairdryer? A pistol? A rubber boot? Something unknown and totally unexpected that I’ll pre-label “schizophrenia”?)

.3

Next in the history of autism came two more Box-Examiners who laid the foundation for the twenty-first conception of autism, the very conception we find enshrined in the Bible of Psychiatry, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Each of these two men attempted to build upon Bleuler’s observations. Remember, Bleuler wasn’t studying boxes containing autism. He studied boxes believed to contain what he called “schizophrenia.”

The first of these two men became influential in America. Leo Kanner, a psychiatrist, did not initially propose the existence of a new category of merchandise. He respected Bleuler’s notion of schizophrenia and believed he was merely expanding upon one of Bleuler’s schizophrenic symptoms—the symptom of “autism.” In 1943, Kanner published “Autistic Disturbance of Affective Contact” in which he examined eleven children, 8 boys and 3 girls, and suggested they possessed the following observable symptoms in common:

“Anxious desire for the maintenance of sameness.”

“Limitation in the variety of spontaneous activity.”

Echolalia.

Large heads.

Clumsy gaits.

Obsessiveness.

Stereotyped behavior.

A failure to react to parental embraces.

Difficulties with eating.

“Masturbatory orgastic gratification” that could arise from, for instance, watching a bowling ball knock down pins. (This psychosexual symptom was based upon Freudian speculation regarding what lay inside the box.)

Another highly impactful observation Kanner made was that children who exhibited these symptoms came from highly intelligent parents whose marriages were “cold and formal affairs” with “parents, grandparents, and collaterals strongly preoccupied with abstractions of a scientific, literary, or artistic nature, and limited in genuine interest in people.”

Kanner went on to co-found and edit the first academic journal devoted to the study of the dark gift, The Journal of Autism and Childhood Schizophrenia, which initially maintained Bleuler’s notion that autism was a symptom of schizophrenia rather than a distinct neural condition.

The second of the two men became influential in Europe, and much later in America. Hans Asperger was an Austrian neurologist who proposed a different collection of behavioral symptoms predicated upon Bleuler’s notion of schizophrenia. Ironically, Asperger proposed these symptoms represented an entirely distinct “personality disorder” he called “autism.” Ironic because Kanner did not suggest the merchandise inside the box was “autism”—he called it “schizophrenia”—but Americans ended up calling Kanner’s schizophrenic merchandise “autism” and called Asperger’s autistic merchandise “Asperger’s Syndrome.”

More simply, Asperger thought “autism” was in the box. Kanner thought a subset of boxes containing “schizophrenia” had similar autistic measurements.

But it bears repeating that neither man had the foggiest notion what actually hid inside the boxes they studied, a fact which contributed to the fogginess of clinical psychiatry’s distinction between schizophrenia and autism.

Here’s a list of observable symptoms that Asperger believed autistic brains shared in common:

“The shutting-off of relations between self and the outside world.”

“Special interests, which are often outstandingly varied and original.”

When they enter a room, they are more likely to pay attention to a book, bell, or candle than a stranger.1

“Difficulties in learning simple practical skills.”

Difficulties in “social adaptation.”

“Learning and conduct problems in adolescence.”

“Job and performance problems.”

“Social and marital conflicts.”

“A paucity of facial and gestural expression.”

Deficiencies in “contact-creating expressive function.”

“A special creative attitude toward language.”

“The ability to see things and events around them from a new point of view, which often shows surprising maturity.”

Like Kanner’s assertion about the “cold and formal” families of autistic children, Asperger also made an assertion that would prove highly impactful on future research: “The autistic personality is an extreme variant of male intelligence.”

There’s a lot of rampant nonsense about Asperger in the (inept and ignorant) field of autism research that I hardly care to discuss, considering both Kanner and Asperger were Freudian-style Box-Examiners who never connected their lists of symptoms to anything biological. Contemporary Box-Examiners spend far more time lazily arguing over whether Kanner or Asperger (both writing in the 1940s!) was more admirable or correct instead of doing the hard work of opening up boxes and peering at the neural merchandise inside.

But it’s worth noting that Asperger’s approach to autistic children was more thoughtful, compassionate, and optimistic than Kanner’s. Asperger wrote:

We are convinced, then, that autistic people have their place in the organism of the social community. They fulfill their role well, perhaps better than anyone else could, and we are talking of people who as children had the greatest difficulties and caused untold worries to their care-givers.

Further, we can show that despite abnormality, human beings can fulfill their social role within the community, especially if they find understanding, love, and guidance.

Let’s review:

Bleuler observed a collection of behaviors that he concluded represented “schizophrenia” (the merchandise he guessed lay inside the box). For Bleuler, autism was one of many observable symptoms of “schizophrenia.”

Kanner and Asperger looked at the boxes that Bleuler declared contained “schizophrenia” and each observed a subset of boxes with distinctive measurements that suggested to them that a different and perhaps entirely novel category of merchandise lay hidden inside.

But none of these men—not Bleuler, not Kanner, not Asperger—ever attempted to open the boxes. Like Freud, they deployed no math nor biology to connect the shape of the boxes to the merchandise inside.

They just guessed.

And here is the great tragedy and comedy of autism research, particularly in the United States: from Kanner and Asperger until right now, mainstream academics and clinicians have argued endlessly about these competing lists of symptoms believed to be indicative of autistic brains.

But all any of these future Box-Examiners had to go on was the boxes themselves. Not the merchandise inside—the brain structures and their neural dynamics—which remained invisible and unknown.

.4

Next in our story we discover exactly why behavioral observation ungrounded in biology or neural dynamics is so risky and vulnerable to mischief.

Kanner’s proposed “autistic” symptoms were explicitly adopted by Freudian psychoanalysts, who by the 1950s and 60s had taken over all of academic and medical mindscience in America. One of these Freudian Box-Examiners was a fellow named Bruno Bettelheim. He ran a frighteningly named “Orthogenic School for Troubled Children” that gave children “parentectomies.” It makes me think of the intercision machine employed by the General Oblation Board in His Dark Materials to cleave children from their souls.

Building on Kanner’s observation that the families of autistic kids were “cold and formal,” Bettelheim blamed parents for their children’s autism. He notoriously declared:

The difference between the plight of prisoners in a concentration camp and the conditions which lead to autism and schizophrenia in children is, of course, that the child has never had a previous chance to develop much of a personality.

In other words, the parents of autistic kids are worse for the kids than living in a concentration camp!

Bettelheim proclaimed that mom was the worst offender of the sort of concentration camp-style parenting that led to autism. He labeled her a “refrigerator mother”: “a mother who is unable to express warmth and love to her child.”

My own mother and father and uncles and aunts all grew up autistic during the era when the notion of “refrigerator mothers” and blaming the parents dominated mainstream psychiatry. I remember getting taught about “refrigerator mothers” in college as a legitimate theory. Back then there was as little hope for ordinary folks to stand up to such ignorant views as there is today: scientists and doctors wouldn’t say such things if they didn’t know what they were talking about!

Asperger’s work also lead to embarrassing convictions about autism that lasted all the way into the twenty-first century, such as the mainstream theory that autism is due to a “masculinization of the brain.” This belief still lingers on today, even after we opened the box and identified the true autistic neural merchandise inside.

The “masculinization of the brain” theory originated in Asperger’s 1944 paper where he declared that autism might be “an extreme variant of male intelligence.” A conjecture proffered in an era with strong cultural biases about the suspected biological differences between men and women, and zero knowledge of the actual differences between men and women’s brain structures and neural dynamics. An era with strong cultural biases regarding gender differences in intelligence and mental aptitude and, once again, zero actual knowledge of the neural dynamics that embodied mental functions.

In other words, Asperger’s assertion about the hidden biology of the brain—about the merchandise inside the box—was pure Freudian-style speculation, ungrounded in physiological fact. As valid as Freud’s conjecture of an id and superego duking it out for control of the ego.

Yet, famous twenty-first century researchers took up Asperger’s conjecture and attempted to show that “extreme” male biology might be responsible for autistic behavior. Though one might question what physiological axis could credibly represent the notion of “extreme male biology,” to their credit, the leading proponents of this theory actually tried to open up the boxes believed to contain “autism” and peer at the biology inside. Specifically, they looked for evidence that testosterone (believed to contribute to “male intelligence,” whatever that was) was higher in autistic children’s brains or their fetal environment than in those of non-autistic children.

No causal relationship was ever demonstrated between testosterone and autism, despite plenty of effort.2

Nobody found special male merchandise inside boxes purported to contain autism. There’s as much evidence supporting the masculinization of the brain as there is for refrigerator mothers.

.5

Let’s get to the most disheartening and tragic consequence of generations of reliance upon Freudian-style Box-Examination. The contemporary diagnosis of autism.

If you or a loved one has been diagnosed with autism, this section reveals where that diagnosis came from.

It’s difficult to conceive of a book with greater practical impact on the lives and opportunities of Americans than the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The DSM dictates:

Who society considers mentally ill and who is considered mentally healthy.

Who gets medical treatment and who does not.

Who gets access to educational resources and who does not.

Which psychoactive drugs may be approved and manufactured and produce vast profits.

Which courses and training programs are taught in medical schools, graduate schools, and nursing schools and who gets hired to teach them.

What sorts of struggling individuals should receive payments from health insurance companies, and how much insurance companies should pay.

How schools and universities handle problem students.

How the military recruits, manages, and treats warfighters and veterans.

Trillions of dollars are bound up in the DSM’s lists of symptoms defining each purported mental illness, including autism. And here’s the dirty secret of the latest edition of the DSM, the DSM-5, which is very dirty and not particularly secret:

Many of the diagnoses in the DSM-5, including autism, are lists of box observations without any knowledge whatsoever regarding the merchandise inside.

Without any knowledge of what’s inside an autistic brain.

I got a special behind-the-scenes look at the making of the DSM-5 while co-authoring the book Shrinks with Jeffrey Lieberman, who at the time was the president of the American Psychiatric Association and in charge of the implementation and rollout of the fifth edition of the DSM. We had unfettered access to everyone and everything going on with the construction of the DSM-5, including activities and controversies never made public.

In other words, I got an intimate, back-of-the-factory look at how the diagnostic sausages were made.

Here’s a very brief recap of the history of the DSM. This recap is essential to read if you wish to understand how doctors and psychologists test for autism in 2024. There’s only one thing that matters in this recap:

At no point in the history of the DSM did the diagnostic criteria for autism ever get based upon anything other than box measurements. There was never a moment when the makers of the DSM looked inside the box—looked inside the brain—to identify any sort of physiological basis for autism. As we will see, every subsequent edition of the DSM simply re-jiggered and diddled the same mathless, biology-less lists of symptoms that were originally proposed, Freudian-style, by Bleuler, Kanner, and Asperger.

Twenty-first century clinicians and researchers are led to believe that, somewhere along the line, some sort of biological ground truth must have made its way into the diagnostic criteria. Surely it’s not the case that everyone is simply using their personal intuition regarding which observable symptoms might hypothetically correspond to a speculative set of neural dynamics, the way Freud did in the 1890s.

But the boxes speculated to contain autism were never opened.

At least, not by the Box-Examiners in charge of the DSMs.

The first two editions of the DSM, published in 1952 and 1968, were 100% straight-up Freudian. Exclusively designed by Freudian psychoanalysts, and almost exclusively used by Freudian psychoanalysts—though most of these Freudians, empowered by Freud’s own rejection of biology and math, felt themselves fully capable of deciding for themselves which symptoms corresponded to which conjectured mental illnesses. They were even free to invent new mental illnesses! After all, that’s what Kanner and Asperger did! Freudian psychoanalysts examined each box according to their own personal intuition to decide what merchandise lay inside, an approach encouraged and justified by the DSM-1 and 2.

Some mentally ill merchandise, according to the DSM-2, included:

Homosexuality.

Asthma (a “psychophysiologic respiratory reaction”).

Hysteria.

Transvestitism.

Delirium.

General fatigue and weakness (“neurasthenia”).

The DSM-2 contained no specific notion of autism. Autistic children were categorized as “schizophrenia, childhood type,” following Bleuler and Kanner.

Then came a true medical revolution of historic proportions. The third edition of the DSM in 1980.

.6

The DSM-3 marked the biggest revolution in the history of mental illness diagnosis and treatment, the biggest revolution in the power and finances of psychiatry, and the biggest revolution in the diagnosis and treatment of autism.

Though the DSM-3 is also widely heralded as a scientific revolution, this is heavily overstated. Scientifically, the DSM-3 revolution ended up doing as much harm as good, though the bold instigators of that welcome revolution are not to blame for its tragic outcome.

The smart, talented, and politically savvy leader of the DSM revolution—the great Robert Spitzer, editor of the DSM-3—forcefully tossed out every last shred of Freudian psychoanalytic influence in the DSM and ushered in the sort of scientific transparency, citations of peer-reviewed publications, and consensus-building that had been utterly lacking in the first two editions. Indeed, to get the Freud-free DSM-3 approved, Spitzer had to battle and defeat head-on the most powerful constituency of twentieth century psychiatry: well-paid Freudian therapists.

Spitzer believed, with justification, that he was lifting psychiatric diagnosis out of the dark ages of Freudian pseudoscience and placing it on firm scientific ground. But it behooves us to consider the cold hard reality that followed his admirable hopes and dreams.

Just consider the diagnosis of autism.

Autism made its first named appearance in the Bible of Psychiatry in the DSM-3 in 1980. The diagnosis was based upon the (mathless, biology-less) ideas of Kanner and Asperger. It was called “infantile autism” and reserved only for children. This was largely due to the fact that Bleuler, Kanner, and Asperger exclusively formulated their symptom lists by studying children. Nobody had a clue if autism persisted into adulthood—nobody was measuring adult-sized boxes.

Reflecting the absence of any physiological basis for “infantile autism,” the DSM-3 introduced the “lunch menu” concept of autism diagnosis:

Choose any two appetizers from the restaurant menu, one entree, and one dessert: now you’ve got your lunch! The DSM-3 said, choose any two “social interaction” symptoms from the menu, one “communication” symptom, and one “sterotyped behavior” symptom: now you’ve got your infantile autism!

This bizarre and, as the science would soon show, highly unreliable approach to diagnosis was a direct result of the fact that there was no biological or mathematical knowledge of what was going on inside autistic brains. There was no rational, principled way to make the leap from measuring boxes to identifying the merchandise inside. All that was available was endless lists of box measurements that were endlessly fought over by folks with different agendas and ideologies and no physiological facts.

So the political compromise in the DSM-3 was to fudge it.

Okay, we’ll say autism is inside boxes that are long and narrow with red packing tape and make a rattling sound AND inside boxes that are squarish with reddish-brown packing tape and make a hissing sound AND inside boxes that are long with reddish-brown packing tape and smell like fish AND…

Spitzer was fully aware of the limitations of this lunch menu approach, but what he hoped and dreamed was that by grounding future psychiatric diagnosis in the principles of transparent, consensus-based science, diagnosis based on box-observation speculation would eventually be replaced (through research) with diagnosis based on open-box neural dynamics.

If the DSM had been a typical scientific publication, like a peer-reviewed journal, Spitzer’s hopes and dreams might very well have come to fruition. Unfortunately, the DSM-3 proved itself an utterly unique document without scientific precedent.

Like Sauron’s Ring of Power, the DSM-3 immediately bound together massive trillion-dollar institutional stakeholders: hospitals, clinics, universities, therapists, funding agencies, public schools, pharmaceutical companies, insurance companies, the military. They all embraced the new and improved DSM-3 and swiftly anchored their complicated bureaucracies, expensive processes and procedures, courses and seminars, insurance claim criteria, drug development programs, diplomas, therapeutic measures, and veteran health care to the diagnostic criteria listed in its pages.

The consequence of huge sectors of society all tying themselves to the words in a single book is that it became politically and financially impossible to make significant changes to the diagnostic criteria of most mental disorders, including autism, without leading to (justifiable) howls of protest from these massive institutions. Though science is free to change with research—new discoveries are often taken up quickly by the scientific community—after the DSM-3, diagnosing mental illness no longer enjoyed the same freedom of transformation and upgrading. The DSM became more like the Federal Reserve: prizing stability, transparency, and gradualism for its trillion dollar stakeholders, and above all, no sudden changes.

Such as the drastic changes that would inevitably result from switching diagnostic criteria from behavioral observations to biology.

The DSM-1 had perpetually anchored psychiatric diagnosis in explicitly Freudian concepts, such as neurosis. It took a revolution to overthrow it. Spitzer’s revolution was possible because there was not nearly the same level of institutional or societal investment in the DSM-2 that arose with the publication of the DSM-3.

But the exact same stagnation and stasis that once plagued Freudian psychiatry now paralyzed the DSM. And the biggest drivers of this paralysis was the fact that so many diagnoses were based upon measurements of boxes rather than the merchandise inside.

.6

There’s one other monumental and tragic consequence of Spitzer’s DSM-3 revolution, especially for those of us fitted with the dark gift. Just as the DSM-1 and DSM-2 had provided scientific credibility, medical credibility, and social respectability to Freudian methods and notions, such as the idea that homosexuality was a mental illness and that moms were to blame for their kids’ autism, the DSM-3 provided scientific credibility, medical credibility, and social respectability to the (still Freudian!) notion that behavioral observation trumps biology when it comes to diagnosing mental illness. Just as psychiatrists could, and did, go on television to blame parents for their kids’ autism, schizophrenia, and depression, today psychiatrists can go on social media and proclaim that this or that set of observable symptoms are indicative of autism, even though they’ve got as much science supporting such views as the Freudians did.

And future mental health professionals—maybe you!—are taught to think and believe this way and then they get into positions of authority and affluence and, like those well-paid Freudian therapists who fought Robert Spitzer tooth and nail, they have no personal or professional interest in opening the box.

To make plain the fact that autism diagnosis got trapped in 1940s conceptions rooted on nineteenth century methods, let’s quickly survey the entire progression of autism research and diagnosis from 1911 until 2024.

In 1911, Bleuler said:

Schizophrenia is what I guess we’ll find inside long and narrow boxes with red packing tape that make rattling sounds when you shake them.

In 1943, Kanner said:

Boxes with red packing tape often have dented corners and smell like peaches, and I’m guessing we’ll find a special form of schizophrenia inside.

In 1944, Asperger said:

Autism is what I guess we’ll find inside heavy, squarish boxes with red packing tape that smell like peaches.

In 1980, the DSM-III said:

Infantile Autism is what I guess we’ll find inside heavy, squarish boxes with red packing tape AND inside heavy, long boxes with reddish-orange packing tape AND inside long boxes with dented corners that smell like peaches AND inside heavy, long boxes that make fizzy sounds when you shake them.

In 1994, the DSM-IV said:

Autistic Disorder is what I guess we’ll find inside heavy, squarish boxes with red packing tape AND inside heavy, long boxes with reddish-orange packing tape AND inside long boxes with dented corners that smell like fish AND inside heavy, long boxes that make buzzing sounds when you shake them.

Meanwhile, Asperger’s Syndrome is what I guess we’ll find inside heavy boxes with orange packing tape that make fizzy sounds AND long boxes with reddish-orange packing tape that smell like peaches AND squarish boxes with dented corners that smell like fish.

In 2013, the DSM-5 said:

We won’t find Asperger’s Syndrome inside any boxes.

Autism Spectrum Disorder is what I guess we’ll find inside heavy, squarish boxes with crimson packing tape AND inside small, squarish boxes that smell like peaches AND inside long boxes with dented corners that smell like fish and make fizzy sounds AND inside oblong boxes with dented corners that smell like peaches.

The DSM-5 introduced the notion that autism was a “spectrum disorder”—which was an attempt to convert the profound flaws of Freudian-era behavioral observations into something that sounded biological and scientific to the public. It was simply an acknowledgement that we still don’t know what merchandise is hidden inside—a fountain pen? a squirt gun? A light bulb? A toothbrush?—but whatever’s in there, gosh, it sure gets packed up in a wild spectrum of boxes!

The spectrum isn’t the merchandise. The spectrum is the boxes.

Calling the dark gift a spectrum disorder is a way of providing institutional scientific-sounding cover to the fact that you’ve replaced biology with (Freudian-style) behavioral observation.

Of course, if you open the box and see what’s inside—wow! a polka-dotted pumpkin!—now you can eliminate many box measurements once speculated to be useful but now revealed as misguided:

Aha! Those dented corners aren’t from the pumpkin merchandise, they’re incidental damage from shipping the boxes! And look! The color of the packing tape doesn’t matter at all—it can be any color and still have polka-dot pumpkins inside! And wow! That peach smell only arises when a polka-dotted pumpkin is shipped together with Fabreze fragrance spray! The smell doesn’t have anything to do with autism at all! I guess autism isn’t a spectrum!

Once you open the box, the nineteenth-century Freudian method of behavioral observation can finally be put aside and we can narrow the diagnostic criteria to those physically linked to the neural dynamics of autistic brains.

Looks like I’ll need another article to finish up. In the next article we’ll address the notion that autism is a genetic condition, the notion that autism is a form of neurodiversity, and we’ll finally open up the autism box and take a look at the glorious polka-dotted pumpkin inside.

Previous HOW AUTISM IS MADE: 14: The Why Module

Next HOW AUTISM IS MADE: 16. Oh No—Another Social Blunder! Do I have AUTISM?

Interestingly, Asperger cites Kanner to underscore this symptom, quoting Kanner’s notes on a child named Donald, “An invitation to enter the office was disregarded but he had himself led willingly. Once inside, he did not even glance at the three physicians present. . . but immediately made for the desk and handled papers and books.”

The huge problem with this sort of “is biomarker X causally related to autism” research is how the “autistic” subjects are chosen. Remember, all anybody has to go on is box observations, not the merchandise inside. So to test for testosterone in “autistic” brains, one must hope that Bleuler’s or Kanner’s or Asperger’s divergent lists of symptoms actually corresponds to some sort of underlying biological reality. If you’ve chosen the wrong box-observations—if you think autistic children have large heads and are clumsy and are bad at math, when the underlying biological truth is that autistic children can have any size heads and are not clumsy and are good at math—then you can never know if your testosterone-measuring results are right or wrong. What if Asperger’s personally-chosen observations correspond to a variety of underlying neural conditions? The same exact way that a 12 inch box that weighs five pounds could correspond to a wide variety of merchandise? If you then test the merchandise in these boxes for testosterone, when some of the true merchandise in boxes of this size are “scissors” and some are “pliers” and some are “hairdryers” (and you possess no ability to discriminate one from the other), then your results are junk. This is a fundamental problem with Freudian methods of behavioral observation and why many call Freud’s own conclusions pseudoscience. It’s exactly like testing for testosterone in individuals with an Oedipal complex.

Thanks, Jerry. Much more coming! :) A book's worth! :)

Get wise to autism recovery and reversal in my podcast here:

https://soberchristiangentlemanpodcast.substack.com/p/s2-ep-5-autism-vaccine-injury-my-81d