The Recognition Dilemma: The Liberating (& Deceiving) Power of THINGS

How Consciousness is Made Chapter 7

Things may happen and often do——to people as brainy and footsy as you.

.Dr. Seuss, Oh, the Places You’ll Go!Chapter 7

1.

This is a crucial article in our series about how consciousness is made in your brain. The article contains key concepts illuminating the deep mystery of consciousness.

Said mystery being the so-called “hard problem”:

How does It become I?

How does objective, public activity in my brain become subjective, private experience in me?

This article strikes at the ultimate nature of the human soul. The ultimate nature of our existence as purposeful beings in the cosmos.

As one might expect from an article that strives for such cosmic ambition, the insights ahead are somewhat challenging and mind-bendy.

I am truly sorry about this, but I’m afraid the only way to take you through the labyrinth is to stick with the highest common denominator, instead of the lowest common denominator. So much in human civilization resorts to the lowest, because dumbing things down is necessary for big business, mass marketing, mass media, and standardized education. If a product, school, or advertisement is too sophisticated and demanding, you lose customers. You lose money. You’re no longer part of the cultural conversation.

But I should hope it is clear—very clear!—that you won’t get into the maze of souls if you’re looking for the easy way up El Capitan. If you’re hunting for the elevator instead of clawing bare rock, you’ll never ascend to the higher levels.

I am doing my best to explain consciousness using plainspoken prose. But there’s no softening the blow: to understand the deep mysteries of consciousness requires a bit of mental stretching on your part.

That’s because the crux of this chapter is the distinction—or equivalence!—between activity and things. Between subjectivity and objectivity.

Between It and I.

.2

Let’s begin with a quick review of the ladder of purpose.

For bacteria minds way down on the first rung, reality is a turmoil of points.

For bumblebee minds—rung two—reality is a fury of patterns.

Swaggering upon rung three are monkey minds. Their claim to mental power is far more audacious. For third rung minds, reality is a collection of things.

Look at the world about you. What do you see?

At home you might see walls and lights and chairs and books and doors and outlets. At the beach you might see sand and seaweed and plastic buckets and shells and the horizon and fluffy clouds and an inflatable yellow raft swaying on the waves. If you’re on a space station—a fine place to contemplate the profundity of consciousness—you will see hatches and screens and cameras and hoses and pouches and the big blue Earth.

Wherever you are, you see and hear and taste and smell and touch things.

Why is thing-thinking so valuable, such a boon to intelligent purpose? Why does the need to think in terms of things prompt the cosmic emergence of consciousness?

Because of the wondrous versatility of things for enacting a mind’s purpose:

You can combine small things to make a new thing: a bird fashions a nest out of twigs.

You can separate a big thing into smaller things: a beaver chews a tree trunk to make logs for a dam.

You can use one thing to act on another thing: a gorilla shoves a stick down a termite burrow to retrieve juicy bugs.

You can open a thing to get another thing: an otter cracks open a clamshell to eat the meat inside.

You can conceal and store a thing for future purpose: a squirrel buries nuts for the winter.

Perhaps most potently of all, you can compare the size, taste, strength, number, dampness, or fun-making of different things and choose the very best thing for your aim. A chimpanzee selects the most bludgeony rock to use as a nutcracker.

Minds think about things in order to more effectively execute purpose on the environment.

Which also happens to be exactly why lower-rung minds think about patterns and points. To make their purpose stronger! It’s just that thinking about things grants a mind far more power over the world than thinking about patterns.

The single most influential reason why monkey minds (including fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and non-human mammals) are so much smarter and more capable than bumblebee minds (including jellyfish, worms, crabs, and insects) is because monkey minds treat their environment as a collection of distinctive, manipulable items rather than a cloud of ghostly textures.

For minds on the third rung of the ladder of purpose, thinking is quite literally thinging.

.3

So then. What, precisely, is a thing?

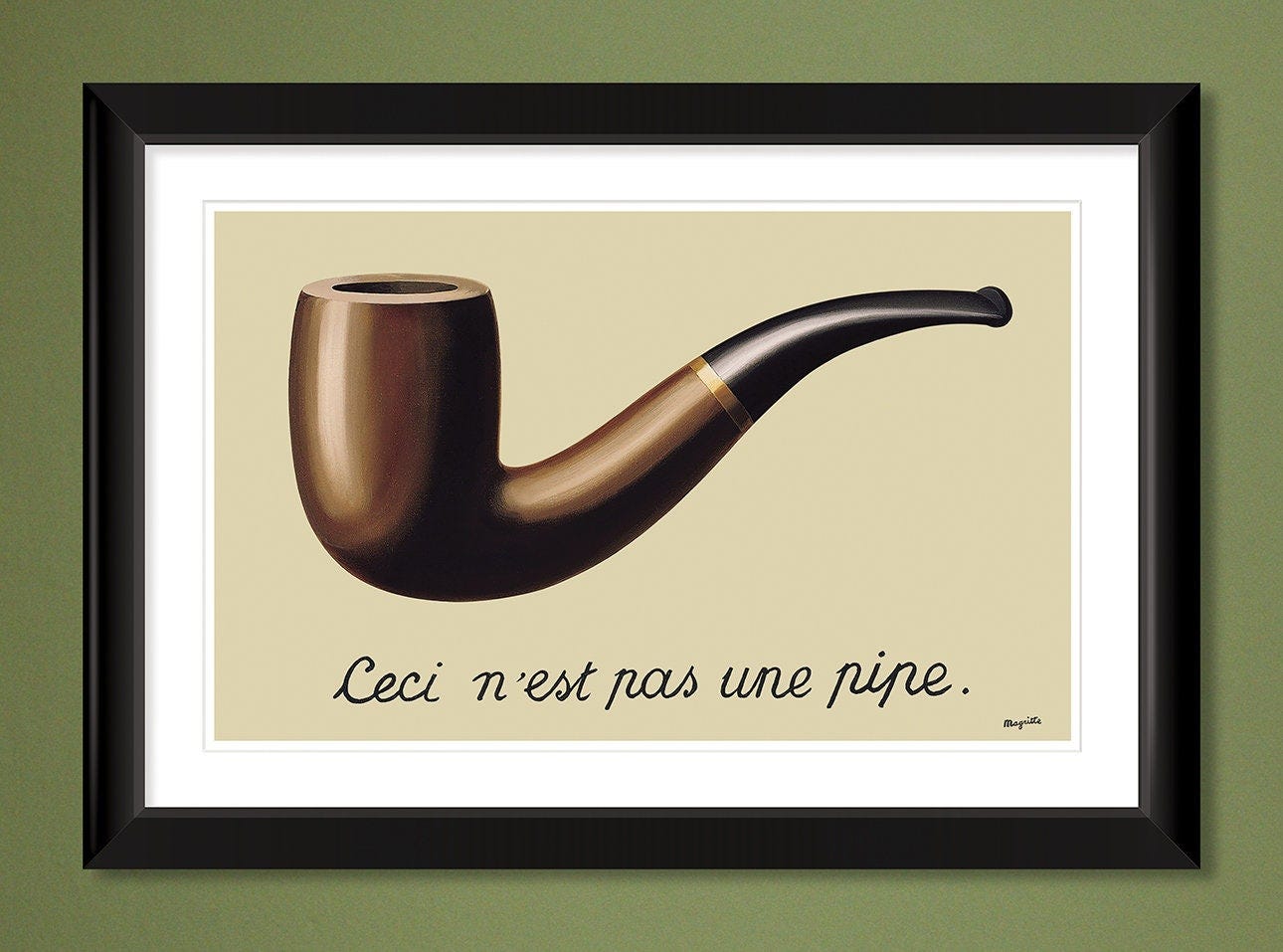

The natural human response to this question is to assert that a thing is “a physical object in the world.” But that instinctive response led human scientists into foggy misconceptions about consciousness (it can’t be a thing! so it must be divine! or impossible!), not to mention centuries of atrocious (and mathless) mindscience.

To understand what a thing is doesn’t require physics, material science, or a philosophy of objectification. Here’s the Cosmic Truth of thingness:

A thing is a mental construct. A thing is a pattern of activity in a brain.

A thing isn’t out there. It’s (tapping my cranium) in here.

You will never find a unicorn foraging in the woodlands of Oregon. But you will find unicorns prancing through human minds, vivid things that most people can easily describe (silky white mane, twisty golden horn, manure that sparkles like a rainbow) and express feelings about (oh how I’d love to brush and stroke that plush-furred unicorn before grilling up some ‘corn steak!)

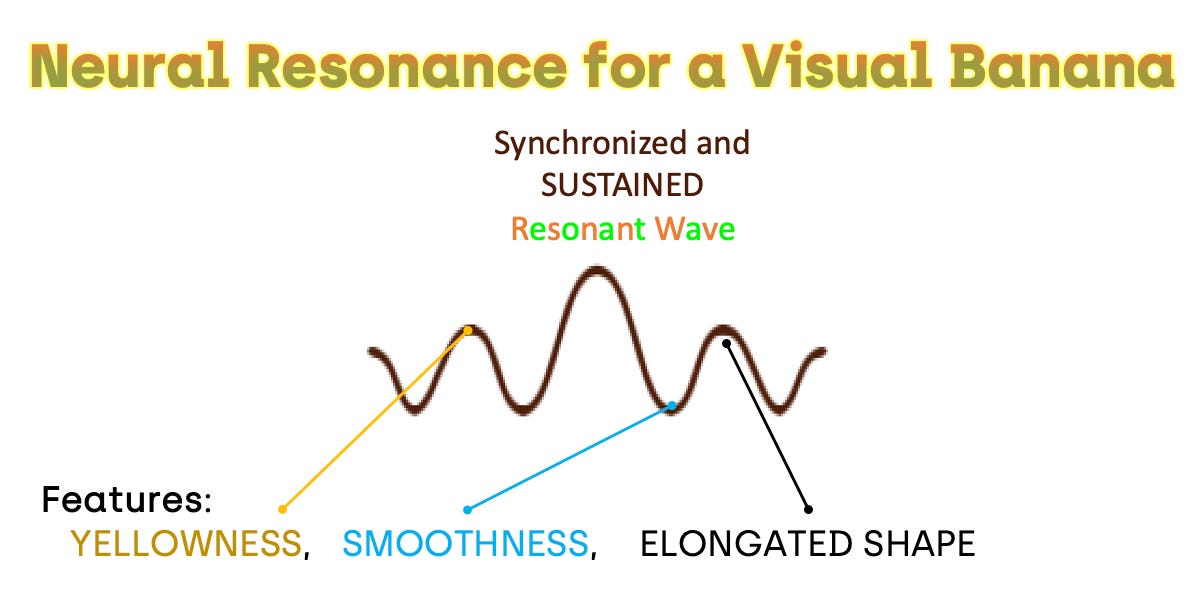

To understand what a thing is, we must understand the neural patterns of thingness. We must examine the mechanical patterns of thing recognition activity in the brain. Every “thing” you’ve ever been conscious of was embodied not in a physical object “out there,” but in a special form of activity in your brain. This thing-recognizing activity has a name.

Resonance.

Resonance converts activity into a thing.

What a cosmic marvel, is resonance! To convert something ephemeral and transitory into something solid and distinct and enduring! For what is the difference, the ultimate cosmic physical difference, between activity and things?

Duration.

The difference between activity and things is their tenacity in time.

The difference between activity and things is the difference between a digital roadside sign that flashes “CONSTRUCTION ZONE AHEAD!” one time only and a sign that displays the message continuously all day long from morning until sunset. A sign that flashes once will only be useful for a driver who happens to be passing at the exact moment it flashes. A sign that is continuously on allows all passing drivers to make use of it.

.4

Things are stable and persistent and enduring. Activity, in contrast, happens then fades.

Resonance is an enchanted process in the brain that takes transient, everchanging activity as its input and converts it into a stable, enduring thing as its output. A stable and enduring and entirely physical thing located in your brain: a resonant wave.

You can think of resonance as “frozen activity” in the brain.

It is the very stability of resonance, its enduring persistence over time, that gives rise to our subjective in-our-soul experience of thingness.

Recall from the “Resonate, My Lovely” article that resonance occurs in a brain when expectation activity matches perceptual activity in one of the brain’s consciousness-generating modules. (Such as the visual What module, whose mission is to figure out what is this thing I see?). As long as (brief, transitory) expectation activity is resonating with (brief, transitory) perceptual activity, their synchronized pattern of activity endures within the brain.

The resonance persists.

Without resonance, the expectation activity and perceptual activity would quickly dissipate into thin air like a summer breeze. Resonance converts the fleeting activity of perception into a stable, lasting, and conscious thing.

Like a tornado.

But how? And why?

.5

How does the objective thing-in-my-brain relate to my subjective experience of the thing-in-the-world? Put another way, how does stable neural resonance in my skull transform into a big juicy banana in my personal awareness?

When you are aware of a thing—a banana, say—what precisely are you aware of?

You are aware of its features.

Oh glorious features! If consciousness is music, then features are the notes. The key to understanding thing-thinking in monkey minds—and the deep nature of consciousness—is to understand the role of features in the activity of consciousness.

Consider the features of a banana. You are aware of it yellowness. Its smoothness. Its elongated shape. You are aware of its soft, mushy interior. Its yellowness, smoothness, length, and mushiness are all features—conscious features—of the banana. You can mull over a banana’s yellowness—actually, look! It’s turning a little black! You can ponder its shape—kind of like a boomerang!

So now our question How does public activity in my brain get converted into private experience in my awareness? can be reframed as How does objective resonance get converted into subjectively experienced features?

This is another way of formulating the (so-called!) hard problem of consciousness: I am willing to believe there is resonant activity in my brain, but I simply cannot grasp how I experience yellow mushy sweetness out of that resonance! It’s impossible!

It turns out that neural resonance exhibits a very special physical structure. A structure explicitly designed to help monkey minds resolve the recognition dilemma: What is this *thing*?

The structure of neural resonance also explains how you consciously experience the features of a thing (such as knowing, This thing is yellow, long, and smells fruity!)

So what is the special structure of neural resonance?

All resonant activity in consciousness-generating brain modules is comprised of features.

Each feature has a physical component and a conceptual component.

The actual physical resonant wave in your brain module has distinctive physical features, such as peaks and valleys. Each of these mechanical features corresponds to a subjective, conceptual quality of a perceived thing, such as color or shape or texture. Thus, each objective structural feature (such as specific valleys and peaks) in a resonant neural wave corresponds to a distinctive subjective quality of a perceived thing.

The perceived yellowness of a banana, for instance, is embodied in a “yellowness feature” in the waveform pattern of resonant activity inside your visual What module. The yellowness feature has a different physical structure in the resonant wave than, say, a blueness feature. (Different peaks and valleys in the mechanical waveform of perception activity.)

Before you can become visually conscious of a banana, the expectation activity (“I’m expecting to see a banana in the fruit bowl!”) is compared to the perception activity in your visual What module (“There’s a long blue thing in the fruit bowl!”). If the pattern of expectation activity contains a physical feature embodying yellowness, while the pattern of perception activity contains a feature embodying blueness, then the two activity waves will not physically match on the color feature.

You will not become conscious of a banana, because without a match between expectation and reality there is no resonance in your brain.

.6

You can think of each feature in a resonant wave as a note in a melody.

A musical note is simply an acoustic wave vibrating at a particular frequency. Conscious features of a perceived thing are distinctive waveform patterns vibrating at particular frequencies and amplitudes.

What is a feature? A feature is an element of a thing.

What is a thing? A thing is a collection of features.

Not at all coincidentally, the relationship between a thing and its features is the same as the relationship between a word and its letters. What is a letter? An element of a word. What is a word? A collection of letters.

A word has a meaning, but a letter does not. The letter “q” only has significance as part of a word, such as “queen.” A word’s meaning is derived from the very specific pattern of letters that form the word. Indeed, as we will see later, our brain’s language system processes the meaning of speech using the exact same neural dynamics it uses to identify things from their features, such as bananas.

Change a single letter, you change the meaning of a word. Quack and Quake and Quark have dramatically different meanings, but their physical representation differs by a single letter—a single feature. Change a single feature, you change the identity of a thing. A yellow boomerang-shaped fruit is a banana, but a yellow egg-shaped fruit is a lemon.

Our consciousness of a thing changes as our awareness of its features changes. And as our awareness of features changes, our consciousness of the thing itself changes.

.7

It is very, very challenging for living Earthborn brains to think about the world as a collection of things. It demands a daunting tangle of neural machinery.

In fact, it took around one and a half billion years from the emergence of the first thinking mind on Earth (a single-celled archaea, most likely, who thought about the universe in terms of points) to the emergence of the first mind capable of thinking of things. (A fish mind.)

The ladder of purpose helps us understand why it took more than a billion years to develop thing-thinking, and why expanding Mind’s intelligence and range of purpose requires Mind to ascend the ladder.

First-rung minds (bacteria minds) think about the environment in terms of points. Point-thinking (like a haloarchaea thinking, “The light is brightest THERE!”) is the ultimate intellectual foundation for all minds, for more advanced minds will necessarily build upon the point-thinking of the bottommost rung of the ladder.

And indeed, the second-rung minds (bumblebee minds) built a new layer of thinking—a neural system—on top of bacteria minds’ point-thinking systems (molecular systems). This brand new neural layer organized and united first-rung points into second-rung patterns. Pattern-thinking integrates and exploits point-thinking.

Then third-rung minds (monkey minds) developed a new modular layer of thinking on top of the other two layers. This new modular layer of thinking organized and united second-rung patterns and conjoined them into third-rung things. The thing-thinking of monkey minds integrates and exploits pattern-thinking.

Monkey minds treats the patterns generated by its second-rung layer of thinking as the features of a thing.

This means it requires three physically distinct layers of thinking operating in your brain—molecular, neural, and modular—to experience the simple thought, “That is one tasty-looking banana!”

But why do monkeys need consciousness in order to identify a thing, while cockroaches do *not* need consciousness to identify a pattern?

.8

Monkey minds manage the recognition dilemma (“What is this thing?”) in compartmentalized fashion.

The visual What module, for instance, compares visual expectation activity with visual perceptual activity to see if they match. If they match, you experience consciousness of the matched thing. The two sets of activity—the act of comparison and the resonance that results from a match—take place entirely within the visual What module. The matching activity—the resonant neural activity embodying consciousness—also occurs within the What module.

Put simply, the recognition dilemma is always resolved within a single What module.

There are several types of What modules. Another is the tactile What module (What is this thing I’m touching?). The tactile What module compares your tactile expectation activity (“I expect to touch a banana when I reach into the fruit bowl!”) to your tactile perceptual activity (“I’m touching something hot and oily in the fruit bowl!”) There’s even a rhythm What module in your brain that enables you to tell the difference between a Reggaeton groove and the cha-cha-cha.

How does a What module go about recognizing a thing? By comparing the features in the expectation activity to the features in the perceptual activity to see if they match. The process is much like comparing two melodies to determine if they are the same. Do the pitch, duration, and amplitude of each note in the melodies match up?

You become conscious of a thing (such as a banana) when the perceived features of that thing become stable and enduring through resonance. Crucially, you become conscious of both the thing itself (a banana!) and the features of the thing (yellow, long, smooth!). This is the alchemy of consciousness—the alchemy of resonance: assembling a collection of features that we simultaneously perceive as a single, coherent, stand-alone thing and as a collection of features.

To exist in the universe, things require consciousness. To exist in the universe, consciousness requires features. This deep truth forms the Second Law of Consciousness. Recall the First Law:

All Conscious Experience is Resonant Activity.

Here is the Second Law, etched in granite:

Only Resonant Activity with Features Can Become Conscious Experience.

.9

It is an empirical fact that only neural resonance in your brain with features generates conscious experience. (Recall your exploration of your own consciousness from The Consciousness-Making Modules.)

There are, in fact, modules in your brain that generate resonant activity without features. Such modules do not generate consciousness. One example is the brain module responsible for controlling how your eye jumps from phrase to phrase—including this phrase!—as you read.

This eye-saccading module employs neural resonance, but its brand of resonance lacks any distinctive mechanical features that correspond to subjective qualities. It’s like a song without notes, lyrics, or rhythms. Consequently, you are not conscious of how your brain decides where to jump your eyes while reading.

But why is the Second Law of Consciousness true? Why is it so important for monkey minds to convert unconscious patterns of perceptual activity into conscious things with features?

To answer this, we must first understand that the mental act of recognizing a thing is intermediate activity within the mindwhirl. Recognizing things connects the crucial act of sensing to the crucial act of doing. In order to decide what to do with a brand new set of perceptions, monkey mind must first convert those fresh new perceptions into a stable, enduring thing in the brain: into resonance.

Why?

Because other modules in monkey mind need to decide what to do with the newly-identified thing.

What can you do with a banana? Eat it. Peel it. Hurl its peel on the floor. Squash it with a hammer. Draw on the asphalt with the banana like a soft crayon.

But your What module doesn’t know any of these possible uses of a banana.

Your visual What module can recognize “This long yellow fruit is a banana!” but it doesn’t have a clue what to do with it. To do something with the banana-thing resonating in your visual What module, other modules must get involved.

Your Why module, for instance, might tell you that you’re hungry and you should eat the delicious banana. To eat the banana requires the involvement of your visual Where module. The Where module locates the banana in space so you can grab it. Then your How module uses the banana-thing location from the Where module to actually reach for the banana.

But for the Why, Where, and How modules to do their jobs properly, they require a thing to think about. They require a stable and enduring pattern of resonant activity—with features!—in the visual What module.

This is why thingness exists in the cosmos! Not because the cosmos is naturally made up of things. (O spiritual revelation!) Rather, because a three-layer monkey mind needs a stable collection of features bound together into a unitary physical object (a resonant waveform with stable mechanical features!) so that all of the mind’s various modules can usefully examine and analyze that stable resonant-thing. . . so that you, Monkey Pilgrim, can execute your glorious purpose upon the world.

Let’s say there was no resonance with features in your brain.

Let’s say your visual What module successfully matched expectation with reality—but instead of synchronizing, amplifying, and extending the matching neural activity, your What module instead responded to the match by broadcasting a brief energetic “GO!” signal. This is what many non-conscious modules in your brain do, in fact, including the module responsible for jumping your eyes from phrase to phrase as you read.

But deciding what to do about a particular conglomeration of real-time perceptions requires. . . deliberation.

It requires the careful evaluation of the particular features of a perceived thing. This, in turn, requires those features to be embodied in a mechanical structure that is stable and persistent. The features must be embodied within a physical thing that endures.

Maybe something is rushing straight at you. Your visual What module identifies the thing: it’s an animal!

But that’s not enough insight to take effective action. You need to know more.

Is the animal small, like a mouse? Or big, like a lion? Does it look friendly, like a Golden Retriever? Or menacing, like a Grizzly bear? The other modules don’t merely need the identity of a thing (“ANIMAL!”) They need access to the details of the thing—to the thing’s features (“BLOODY AND FOAMING AT THE MOUTH!”)

Your Why module needs to know if the animal is large and menacing or small and friendly. Your Where module needs to know if the thing is moving and how fast and whether there are things between the charging animal and you. Your audio What module might step in and append some additional features to the ANIMAL-THING that the visual What module can’t recognize, such as a low growl or high-pitched yipping. The Why and Where modules can then recognize and exploit these additional features of the ANIMAL-THING, which are all knitted together within a stable multi-module synchronized resonant wave.

Into a multi-modular THING.

For so many different brain modules to perform so many different mental actions based upon the recognition of a single thing requires that both the thing and its features persist without fluctuation so that the rest of the brain has time to access those features and make use of them—or even add to them, as the audio What module did with the charging animal.

That’s why consciousness converts transient neural activity into a stable physical thing in your brain. This is the mechanical secret to consciousness in third-rung minds.

.10

Consciousness converts any resonant activity with features into a thing. Even when the source of the mind’s resonant activity is not a material object.

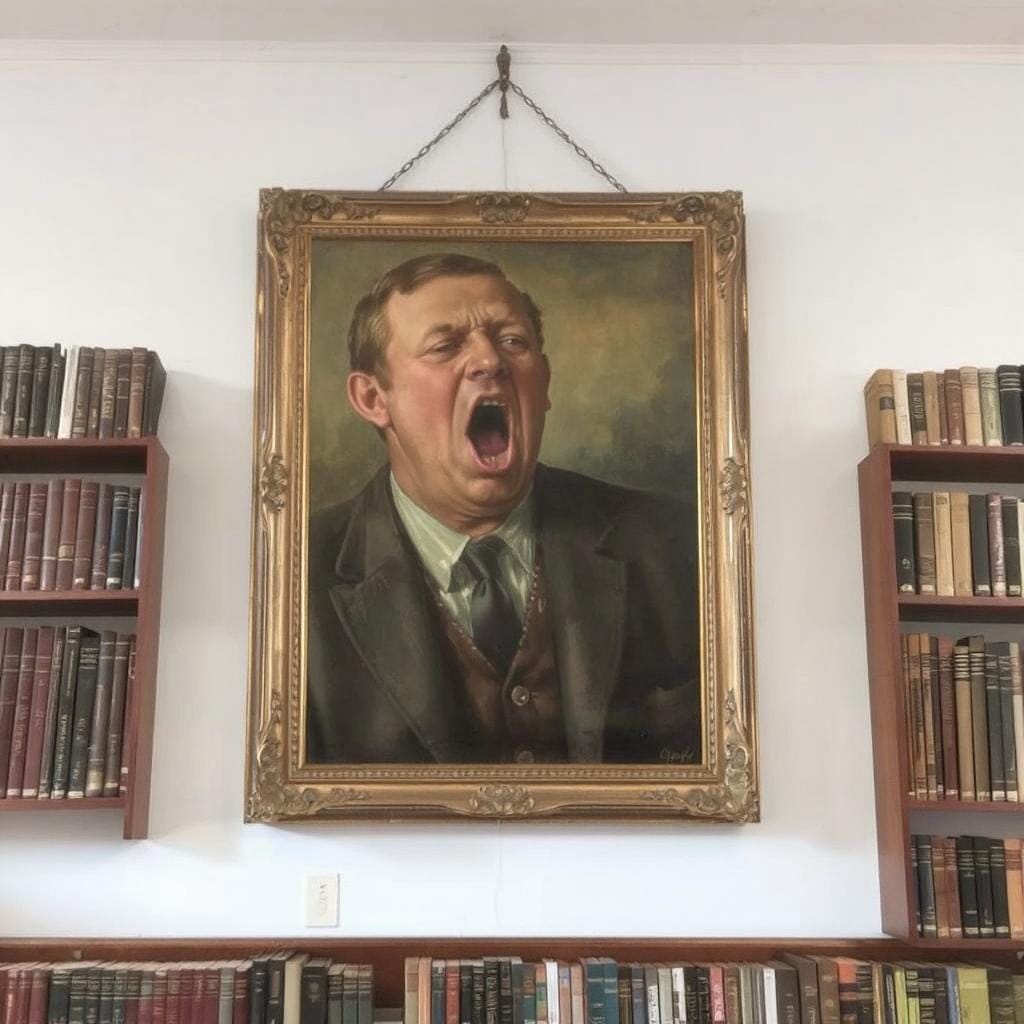

Consider a belch.

A belch is transitory activity. A brief expulsion of air and the rude sound accompanying the outblast.

You can’t put a belch in a box and deliver it to your neighbor. You can’t put a belch in a picture frame and hang it in a museum. Yet, we naturally and unthinkingly treat a belch as a thing possessing the same thingness as a tea kettle.

The word “belch” is a noun, the grammatical marker for thingness. In other words, we psychologically and linguistically conceive of an ephemeral, fleeting noise as a lasting material object.

We can photograph someone belching, for instance, and title the photo “The Great Belch.” And then hang it in the museum.

Which is a pretty good metaphor for what consciousness is doing in our brain.

Even though the actual belch in the photograph is invisible, our brain adds the visual features of the belching man’s gaping mouth to our conscious notion of the (invisible, silent) belch in the photo. A comic artist might draw a plume of green gas coming from someone’s mouth to convert our subjective experience of a fleeting audio feature into a stable visual feature.

By converting the evanescent act of a belch into a concrete thing, our consciousness empowers us to count belches, record the duration of belches, or rationally compare the volume or moistness or repugnance of two belches with our colleagues, debating the finer points of eructation with mechanical precision.

The reason we can perform these powerful intellectual activities upon a belch is not because a belch is a physical object. We can do these actions because our brain—our consciousness—converts the transitory activity of a perceived belch into a stable, enduring pattern of resonance.

We accept a silent photograph labeled “The Great Belch” as authentic without qualms—even though it certainly isn’t a belch, it’s a painting!—because the visual What module recognizes the facial configuration associated with belching and resonates on the (imaginary!) visual thingness of a photographed belch, which then allows the auditory What module to imagine the sound of a belch and add these (imaginary!) auditory features to the recognition resonance of the belch in the visual What module.

Converting transitory environmental activity, such as belches, sneezes, explosions, avalanches, rainfall, looting, mating, floods, dances, and slam dunks into things is a very powerful form of thinking because it allows our mind to render all perceptions, no matter how transitory or invisible or abstract, into stable patterns of activity that can then be acted upon by all the modules in our mind.

Our brains compare apples and oranges all the time because we can compare the features of any two resonating things in our brain. By comparing features, we can decide which belch is more gross, more fun, or more indicative of underlying disease.

We can even ponder the infinitesimal or the infinite by converting them into things, inviting us to name and evaluate their stable and enduring features. We can generate a mathematics of the infinitesimal, a story about the eternal, or suggest with rational arguments that the infinitesimal and the infinite are one and the same. We can even draw conclusions about the physical universe from such contemplation—even though the infinitesimal is as imaginary as a unicorn, a mere pattern of neural activity in our brain.

Perceiving the world as a collection of things is the great triumph of monkey mind, and one of the prime reasons for the existence of consciousness. But there is a downside to thing-thinking. A downside to carving the universe into stuff.

.11

Our thing-focused consciousness automatically and unthinkingly makes us consider genuine activities in the world as things, even when we’re better off thinking about such activities as activity.

Indeed, this shortcoming of thing-thinking has probably been the number one intellectual fallacy plaguing scientists from Isaac Newton until today. Historically, scientists in most fields of research start out treating all phenomena under their new purview as things—simply because that is what our untrained brains naturally insist to us! Because our brain instinctively and automatically carves up the world into things. Even scientific brains.

Fortunately, the scientific process eventually (and always!) reveals that what our mind insisted are things are more usefully treated as activities.

Physicists initially believed that heat was a thing called caloric—a liquid believed to move from hot places to cold places. Eventually, physicists realized that heat was the collective activity of matter.

Chemists initially believed that fire was a thing known as phlogiston—a substance concealed inside all matter that gets released when heated. Eventually, chemists realized that fire was the collective activity of matter.

Biologists initially believed that life was a thing known as elan vital—enchanted energy that dwells inside all living creatures. Eventually, biologists realized life was the collective activity of matter.

Many prominent mathematicians throughout history have believed that math exists somewhere as “real things.” That the integer five, imaginary numbers, and polynomial equations all exist as perfect entities “out there” in some ethereal Platonic realm that is accessible, via unknown means, by mathematical minds. But mathematics and its objects of study are just the collective activity of minds.

And, yes, in my own field of mindscience, scientists initially believed—and most still believe!—that consciousness is a thing. The clueless philosopher who initially proposed that consciousness was an unsolvable “hard problem” (a benighted proposal he put forth a full decade after Stephen Grossberg had already identified the physical basis of consciousness) explicitly claimed that consciousness was a fundamental “thing” in the universe, like caloric, phlogiston, and elan vital.

Perhaps now you can appreciate the irony of this philosophical misconception. The whole reason our conscious brain tells us that consciousness itself is a thing (amusingly, like any narcissist, our brain tells us that its consciousness activity is an impossibly mysterious thing!) is because of the thing-making activity of consciousness itself.

The neural activity that embodies conscious experience is converted into stable thingness through resonance. As with heat, fire, and life, consciousness is also collective activity. The collective physical activity of three mechanical layers of thinking: molecular activity, neural activity, and modular activity.

Because consciousness makes us experience every perception of our universe as a thing with features, we instinctively perceive our own consciousness as a thing, too. We can’t conceive what this thing might be (any more than we can conceive of what elan vital might be, or caloric, or phlogiston), so we surrender to our brain’s irrepressible thing-thinking and classify the existence of consciousness as a great mystery. As a hard problem.

Because how can a thing be me?

The thingness that consciousness creates for us is resonance. The incarnation of transient neural activity into a stable and enduring mechanical structure. A structure that is simultaneously a coherent, unitary whole—a thing!—and a stable collection of individual features. A whole and the parts of the whole at the same time, accessible by other parts of the brain at the same time.

Accessible by you at the same time, for you can willfully choose whether to contemplate the banana or its yellow.

We’re getting close to grasping how It becomes I. We now possess one of the key physical insights that will carry us there. But we need others.

We still haven’t crossed that final bridge to see why, precisely, I experience resonant neural activity with features as my personal experience. We need a few more key insights into Mind, the most crucial being how consciousness solves the attention dilemma.

Previous Consciousness: 6. The Three Dilemmas of Monkey Mind

Next Consciousness: 8