Chapter 6

The central dilemma in journalism is you don’t know what you don’t know.

.Bob Woodward, Washington Post journalist.1

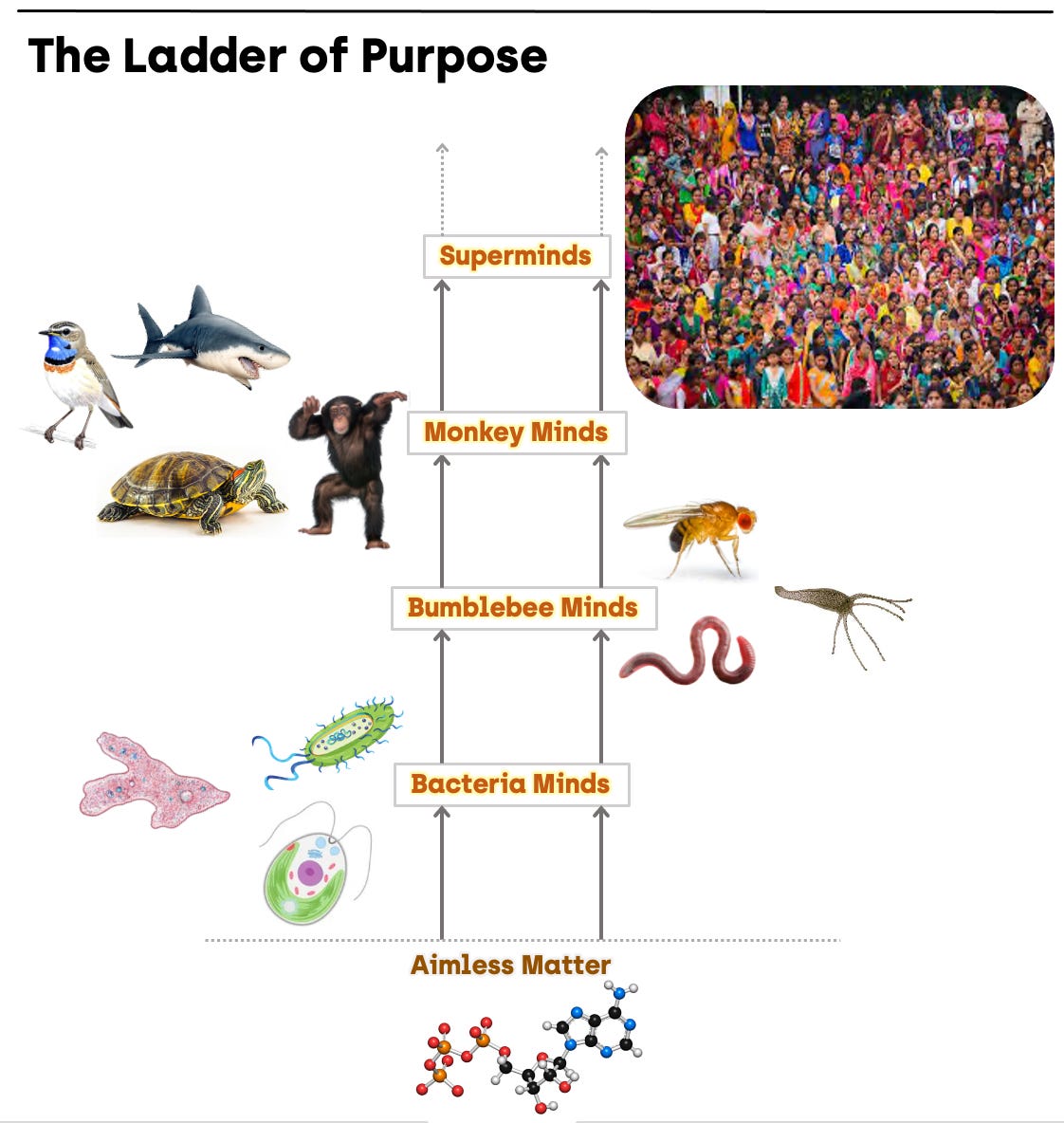

The ladder of purpose is all about thinking bigger.

Bacteria thinking, bumblebee thinking, monkey thinking: minds ascend to higher rungs to attain greater control over a greater range of chaos. Minds think bigger so that they can make better predictions and take more useful actions in ever more complex situations.

Bacteria minds (like amoebas) think small. They think about jots of nutrition and specks of toxin and spots of light. In a word, bacteria minds think in terms of points.

Bumblebee minds (like the spotted lantern fly) think bigger. They think about odors, surface geometries, and the visual flow of flight. Bumblebee minds think in terms of patterns.

Monkey minds (like orangutans) think bigger still. They think of stone nutcrackers, oak-branch cudgels, and secret stashes of sweet bananas. Monkey minds think in terms of things.

Points to patterns to things: this is how minds learn to think bigger. Each new rung of the ladder—each new layer of thinking—expands purpose’s knowledge and reach. But learning to think bigger doesn’t come easy. Stark challenges arise whenever minds attempt to master a broader purview of aimless matter. Some challenges arise from the complexity of physical reality itself—swimming through turbulent water, hopping across sundried scrubland, snatching jittery moths out of the midnight dark. Developing new doers (like scaly fins or elastic tendons or furry wings) and new sensors (perceiving buoyancy or dryness or acoustic radar) requires new configurations of neurons, circuits, and modules to manage the elevated complexity of the higher-rung universe.

Other challenges arise from managing bigger and more complicated brains. As minds develop and ascend the ladder of purpose, they confront new mind-wide problems known as mental dilemmas. Monkey minds (including the minds of parrots, toads, and catfish) must resolve three grand dilemmas in order to think effectively about a world full of things.

If we hope to understand why consciousness exists—why evolution designed the brain to experience conscious awareness—we must learn about the three dilemmas of monkey mind.

.2 The Mental Dilemmas

A dilemma is a trade-off. You can have more of this, but then you’ll get less of that. If you travel north, you can’t go south. If you put on sneakers, you can’t wear flip-flops. You can’t have your cake and eat it, too.

The most crucial thing about dilemmas is they’re unsolvable. They offer no perfect way to get everything you want. A dilemma always involves choice. Box up the Oreo cheesecake for later? Or gobble it down right now?

There are three cosmic dilemmas that arise within any mind straining for the third rung. Why are these dilemmas downright cosmic?

Because these dilemmas arise in every mind in the universe that attempts to think about things, such as donut-shaped rocks and froth-water rivers and peach-colored clouds in the heavens.

And cosmic also because the mind’s management of these three dilemmas is what generates consciousness. The neural activity in third-rung creatures that is explicitly designed to resolve these mental dilemmas is precisely what physically embodies conscious experience.

You experience consciousness while your brain is mechanically resolving these special dilemmas. The specific flow of neural activity that unfolds while your brain tackles these dilemmas determines the precise nature of your private subjective experience.

These three dilemmas are handled proficiently by every backboned beastie on Earth: all fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals are conscious because their brains possess the ability to resolve the attention dilemma, recognition dilemma, and learning dilemma.

.3 The Attention Dilemma

The most vital dilemma monkey mind confronts is the attention dilemma:

What should I focus on next?

Every mind in the universe, even the microscopic minds of protozoa, confronts an attention dilemma. A salmonella bacterium must choose: should I swim toward that food or away from that predator? A fruitfly must decide: should I fly toward that attractive mate? Or toward that heap of dung? A turtle must pick: do I follow the warmth of the rising sun? Or do I slide into that nice cool mud?

The attention dilemma is an urgent problem in all minds, but in monkey minds the attention dilemma becomes exponentially harder to resolve. Monkey minds contain far more thinking elements (molecules, neurons, networks) than bumblebee minds, and every individual neuron, network, and module in a monkey mind nurses its own individual attention. There are billions of neurons in a monkey mind. Thousands of networks. And dozens of modules. And every neuron, network, and module is concerned with its own private monkey business.

Let’s rephrase the attention dilemma for monkey minds:

With three layers of thinking (neurons, networks, and modules) all paying attention to different stuff at the same time, how does the brain decide what to focus its conscious attention on?

The attention dilemma is a matter of life and death. If you focus on your smelly socks instead of the pitchfork lancing at your chest, you’ve handled the attention dilemma unwisely.

.4 The Recognition Dilemma

The second critical dilemma confronting monkey minds is the recognition dilemma:

What is this?

All minds must identify what they are sensing so they can decide what to do about it. The reason recognition is a dilemma is because you can only recognize one identity of a thing: you see an apple or an orange. You hear a violin or a trumpet. You smell a rainbow açai bowl or day-old vomit.

Even a microscopic paramecium must recognize the contents of its environment. Is this drifting mote a morsel of food? Or a fleck of poison? Ascending to the third rung of the ladder of purpose, identifying things is far more treacherous than identifying points:

What is this orange sphere?

Is it a sun?

A basketball?

A citrus fruit?

A baseball dyed orange?

A carrot carved into a ball?

Or a random dollop of paint?

Correctly recognizing an object or event requires sophisticated mental activity. An object might be food, or a tool to find food, or a tool to gather food, or a spice to add to food to make it taste better, or a spice to add to food to kill parasites, or an ally who gathered food with you yesterday and may be willing to gather food with you again today.

In order for monkey minds to act upon a perceived thing, they must correctly identify the identity, location, and/or emotional value of the thing:

It’s a carrot carved into a ball!

There’s a small doo-dad flying through the air toward my head!

There’s an annoying screeching noise!

The recognition dilemma is almost as urgent as the attention dilemma. If you mistake a sub sandwich for a gun—or a gun for a sub sandwich—you can end up in a world of hurt.

.5 The Learning Dilemma

Monkey minds must also resolve the learning dilemma:

Should I remember this thing? Or can I forget it and move on?

Should I remember what I ate for breakfast this morning?

What I ate yesterday morning?

What I ate ten years ago this morning?

Should I remember this white fluffy cloud shaped like the letter “D” drifting through the sky?

The rock I accidentally kicked while gazing at the cloud?

The irate lady cursing me because I kicked the rock at her arthritic knee?

Should I learn how to curse like that angry woman?

You can’t remember everything you experience. Even a mind as potent as monkey mind suffers from limited memory storage. Brains must choose which new objects and events to learn about—and which to ignore. Floods and hailstones and puddles and rockslides and fig trees and hair lice and rotten branches and flatulence and dust storms and assaults from enemies—deciding what to remember and what to forget is simultaneously imperative and formidable for third-rung minds.

.6

During each loop of the mindwhirl in a third-rung brain, all the individual neurons, networks, and modules—all three layers of thinking—must collectively resolve the three dilemmas of monkey mind:

What should we *all* focus on next?

What is this *thing* we’re all focusing on?

Is this thing we’re all focusing on worth *learning*?

Monkey minds resolve the attention dilemma and learning dilemma holistically. Holistically just means “using the whole mind.” The opposite of holistic is “compartmentalized” or “modular”: using part of the mind.

This is crucial: there is no centralized “decider” module that chooses what the brain should focus conscious attention on next. There is no “superintendent” circuit that decides what the brain should learn and what it can ignore and forget. Instead, the attention and learning dilemmas must be resolved, somehow, by special holistic mental activity operating across the entirety of the brain.

You can probably guess what that special holistic mental activity is. . .

(Hint: it rhymes with schmonsciousness. . . )

Previous Consciousness: 5: The Consciousness-Generating Modules

Next Consciousness: 7. The Liberating (& Deceiving) Power of THINGS