How Autism is Made 9: Autism and The Supermind Part I: Shared Attention

At last, a clear explanation of how autism disrupts our social cognition

Remember that it is not just the words used by someone else that can cause difficulty (such as "Go and wash your hands in the toilet"—make sure you wash them in the sink, not physically in the toilet itself!); many of us have an inability to recognize different facial expressions to tell if someone is happy or sad, or to sum up an individual by the manner of their dress sense or leisure-time activities.

.Marc Fleisher, Survival Strategies for People on the Autism Spectrum.1

If there was just one thing I could teach autistic folks to help them understand the true nature of their dark gift, that one thing would be superminds.

Superminds and supermind thinking perch upon the fourth rung of the ladder of purpose. It is the most important rung for autists to learn about, because this is where autism happens. The supermind is where the autistic rubber meets the human road. If you wish to fathom how autism works medically, physiologically, mentally, culturally, if you wish to understand how you and your darkly gifted brain fit into human society and the cosmos, this is the article for you, pilgrim, because this is an introduction to Why Autism Makes Our Life so Hard—and Grants Us Opportunity for an Enchanted Life.

These articles summarize the state of scientific knowledge on superminds and how supermind thinking relates to autism.

Recall there are four layers of thinking found in Earthborn creatures, each corresponding to a rung of the ladder of purpose. At the bottom, beneath the ladder, lies aimlessness. Physics. The first rung consists of the most primitive dynamics of purpose in the universe, bacteria minds, which think using molecules. The second rung is the most primitive multicellular dynamics of purpose, bumblebee minds, which think using neurons. The third rung consists of the most primitive dynamics of consciousness in the universe, monkey minds, which think using neural modules.

Fourth rung is the supermind, a form of thinking that only a handful of apes have attained, including Homo neanderthalensis, Homo erectus, and the only supermind still breathing, Homo sapiens. Superminds think using individual brains. You and me. (Except, not you and me, pilgrim! We’re autistic!)

Whenever you speak to another human, four distinct yet interdependent forms of thinking are all operating in your brain at the same time: bacteria thinking (inside your neurons), bumblebee thinking (inside your neural circuits), monkey thinking (inside your neural modules), and supermind thinking (between your sapien brain and other sapien brains).

In this subset of articles, I’m going to focus on aspects of the supermind relevant for autism and improving your autistic life. I want to help you see why supermind thinking is so crucial for you to learn about if you want to understand why socializing and small talk and basic human connection is so darn hard for us.

.2

Whenever you experience a private conscious thought, two (or more) modules in your brain resonate together. But for a supermind to experience a thought, two modules in two different brains must resonate together.

A great deal of circuitry in the human brain is specifically designed to help two distinct brains come together and resonate as one. Supermind circuitry. This mind-to-mind social circuitry depends fundamentally on the successful operation of the people-painting function of the Why module, as we’ll see in a moment.

There are two dominant forms of mental dynamics that govern supermind thinking and brain-to-brain resonance.

First is SHARED ATTENTION: Getting brains in two (or more) different heads to focus on the same subject.

Second is TRIBALISM. Getting a community of many brains to all think the same way about shared subjects of attention.

We’ll tackle tribalism in the next lesson. In this one we illuminate shared attention.

3.

Shared attention is the oldest and most basic mechanism of supermind thought. It developed in stages over millions of years in many ancestors of Homo sapiens, though shared attention reached its pinnacle in a highly potent form of shared attention unique to sapiens: spoken language.1

Shared attention consists of mental dynamics—brain activity—that guides two separate minds to focus on the same thing at the same time. All shared attention mechanisms cause a physical resonance to occur between two separate brains. Let’s review the historic stages of shared attention to understand how supermind thinking works—and why autism disrupts shared attention so catastrophically.

Below are the key stages of shared attention that our evolutionary ancestors passed through on their way to building a sapiens supermind (that is, human civilization). Though we can’t be certain of the precise order these stages unfolded historically—some stages may have proceeded simultaneously or in a different order—but these are all well-defined stages of shared attention in the sapiens supermind and each is grounded in specific neural circuitry.

The first stage of shared attention was Eye Gazing.

One primate looked at the eyes of another primate. This wasn’t yet resonant dynamics, but rather a necessary platform to set up mind-to-mind dynamics. To share attention with another soul, first you need to locate and track the window to their soul: their eyes.

Building on top of eye gazing, next came gaze following: looking where another person is looking. Now mind-to-mind dynamics are flowing, though only in one direction: one person is tracking the attention of another person.

Already, after just two stages of primitive shared attention, we can begin to see why autism is so disruptive. Recall the attention dilemma that all minds must solve: what should I focus on now? For humans in a supermind, the answer is often: pay attention to what other humans are paying attention to! That’s what the human Why module is designed to jumpstart: it paints other humans with a magical brush that makes them “pop out” in our awareness as especially interesting and important. After the Why module prompts us to focus on another person, the shared attention circuitry kicks in and causes us to automatically locate the other person’s eyes and then automatically discern what the other person is looking at.

But not in autistic brains. Our brains might focus on a book, a bell, or a candle, rather than another person. To experience eye gazing or gaze following, our brain first needs to prompt us to focus on other humans. If we don’t, even our most basic shared attention circuitry won’t kick in. And there’s a lot more shared attention circuitry to come!

Next comes the first true mind-to-mind resonance: shared gaze. Now mental dynamics—which are physical dynamics, of course—are flowing from brain to brain, linking the visual modules in one mind to the visual modules in another mind. Two different brains focus on the same subject at the same time, and both brains are aware they are focused on the same subject.

Both are aware they are sharing attention.

Autistic folks can certainly experience shared gaze. We just don’t enter the mental state as easily or naturally as non-autistic folks, because the most important orientation mechanism for kickstarting shared gaze—the Why module’s boldface interest in other people—is broken.

Now we’re getting fancy. The next stage of shared attention is shared tutoring, where one person shows another person how to perform some behavior on a shared subject of attention, like how to peel an apple. This appears to be the most sophisticated form of shared attention in our primate brethren, though in a much cruder form than we find in humans. Chimpanzees, for instance, learn how to crack nuts with stones by watching other chimpanzees. This is potent mind-to-mind resonance, though in chimpanzees the teacher does not explicitly focus on teaching the student. It’s more like the mentor tolerates or perhaps welcomes the learner watching, without making any special effort to make the lesson more intelligible.

In humans, shared tutoring usually involves the teacher performing the action in a deliberate manner designed to facilitate learning.

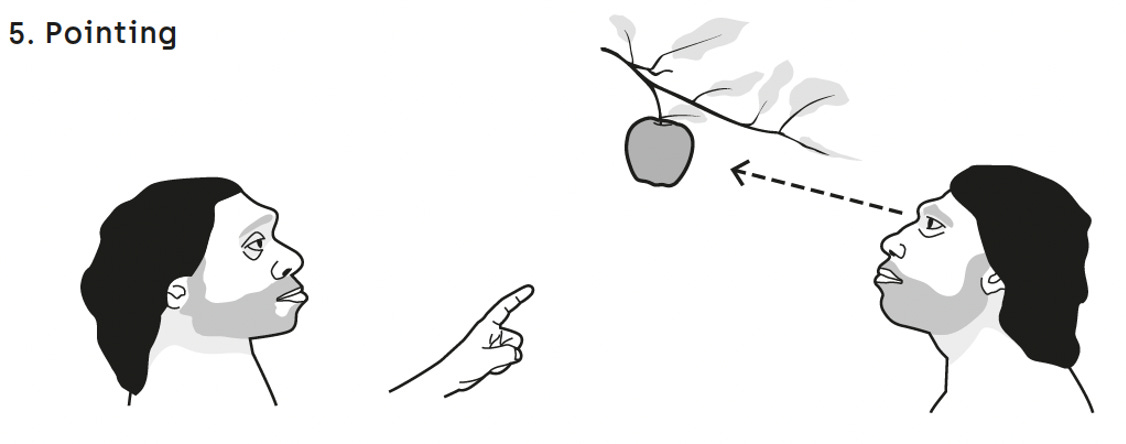

Somewhere in the evolution of shared attention came pointing. Even though shared tutoring might seem more mentally sophisticated than pointing, the empirical facts tell us that the only creature on Earth who instinctively points and knows to follow the direction of a pointed finger is humankind. By one year of age, human beings start pointing, and by one and a half, they point well. Chimpanzees do not instinctively point, and have great trouble learning to look where one is pointing rather than looking at the finger.

Now we’re on the royal road to language. In human brains, the dynamics of gesturing and speechmaking are intimately bound together. All people instinctively use their hands when talking (and many people, including Michael Jordan, instinctively move their tongue while performing manual activity), and all cultures have a rich variety of meaningful gestures and gesticulations, from a thumbs-up meaning Great work! to the middle finger meaning Fudge off to a finger slicing along one’s neck meaning You are going to die!

At some point in our evolutionary past, pointing and gesturing combined to focus shared attention even more tightly on a specific object, such as the apple on that branch (rather than, that branch).

Once pantomimes were established for particular objects with the aid of pointing, the pointing was no longer necessary. You could simply indicate a particular object by making the appropriate gesture, such as a pantomime for “apple.” This is a very sophisticated form of mind-to-mind resonance, which requires two different brains to pay attention to the same idea of a thing without the actual thing itself being present and visible. It means that two different brains must resonate on the same conscious experience and know they are resonating on the same experience, even though the subject of that experience is not present or may even be purely imaginary. (You can make a gesture for “apple” during a time of famine to express what you’re dreaming of eating.)

Note that to attain this impressive level of supermind thinking, where a community of brains can resonate on the same idea without a corresponding physical object being present, we had to proceed through many stages of building brain circuitry for shared attention.

Autism disrupts all those stages.

The miraculous stage! The birth of rudimentary language! Once pantomimes were established for particular meanings—for shared ideas—it became possible to put a vocalization to that pantomime. It became possible to link a phoneme to a concept. This required bringing new motor control modules (for making vocalizations) and auditory modules (for listening to vocalizations) into shared attention harmony with the existing motor control modules (for gestures) and visual modules (for eye gazing, gaze following, observing pantomimes). This is where the human neural circuitry for shared attention and supermind thinking really accelerated past our primate brethren.

The pinnacle of shared attention. The glory and pride of superminds: language. Spoken words. Pure mind-to-mind resonance between modules in two different brains. Two consciousness cartels unite as a single consciousness cartel, when we converse with another soul.

Our ability to speak to one another and understand each others’ dreams, fears, and intentions rests upon millions of years of evolutionary development of shared attention circuitry.

And now you can see why autism crushes our ability to connect with other folks. Supermind thinking—including all forms of social interactions—rests upon exquisite circuitry for shared attention, some ancient, some more recent. . . which in turn rests upon the Why module’s ability to goad us to focus on other humans, especially other folks’ eyes and words.

The dark gift destroys the natural mechanics of shared attention in our supermind-wired brain.

Previous Autism Lesson: 8: The Attention Dilemma

Next Autism Lesson: 10: Autism and the Supermind Part II: Tribalism

Read FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS about Dr. Ogas and the Dark Gift

Other human ancestors likely used verbal or gesture-based languages, too. Neanderthal almost certainly had language, and most of the pre-Neanderthals Homo’s likely flaunted some form of language, too, back to Homo erectus. But only the languages of sapiens have survived.