Maxwell's Game

Intex Part 11: An introduction to the most important and enlightening of the intex riddles.

The cities you live in are like Maxwell’s Demons. They seem to separate the hot and cold, the low and high, the vast and the minute, but at any moment an invisible force might undo the delicate equilibrium.

.Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities.1

If you happen to stumble upon intex, they will set before you certain tests to appraise your mind and soul.

On occasion a test—a question, a puzzle, a riddle, a trial—may be presented to you without comment or context. You may not know it a test until you have passed through it.

Now and then, a test is delivered with some guidance about outcomes. The Riddle of Nine Dots was such a vehicle: intex declared that the nine dots might help me gain some measure of willful control over my transit through the (always chaotic and fearful) maze of souls. The riddle might also clarify world-jumping, was another part of the accompanying guidance.

Rarely a test may be presented expressly as special. As a singular conundrum opening deep doors into the bedrock of reality. One such riddle was explicitly anointed by intex as fundamental. As one that would enlighten pilgrims like me—and perhaps you.

The name of this intex riddle was Maxwell’s Game.

The human version of the game—a thought experiment—was first proposed by the great classical physicist James Clerk Maxwell in 1867. Maxwell is most famous for discovering the equations governing electromagnetism, but his Game has nothing to do with electricity. Or equations.

On my first encounter with intex they showed me their version of Maxwell’s Game, though I didn’t understand it at all. Mostly because high levels of terror and horror interfere with routine cognition.

But again and again intex highlighted Maxwell’s Game during contact until eventually Five spoke of it explicit.

Five proclaimed Maxwell’s Game a test. A test for all sorts of souls. I was informed that Maxwell’s Game was a puzzle for minds that would illuminate the foundational principles of the Commonality.

.2

Though my memory for the past is poor, I can recall the first time I got exposed to Maxwell’s Game. It was my high school physics class. Within my introductory physics textbook was a hand-drawn illustration I still recall. It portrayed a sneering bulbous-nosed imp perched atop two adjacent boxes.

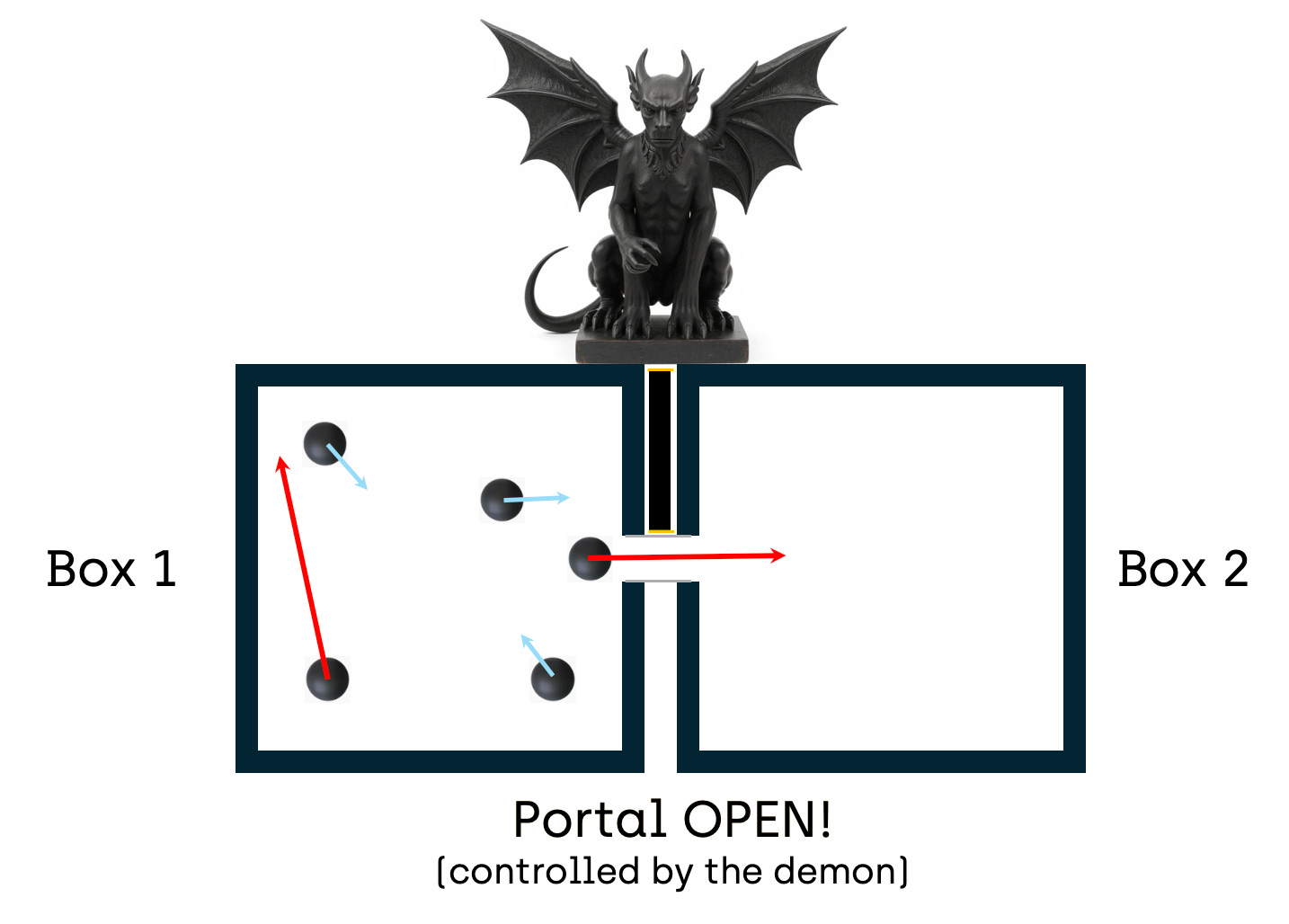

Box 2 was empty.

Box 1 contained a dozen little black balls. The balls ricocheted off the walls of the box as the goblin leered down at them. The balls represented gas molecules. The balls bounced around the box at different speeds. Some slow. Some fast.

The two boxes—one empty, one full—were connected by a portal. The portal was a hole just wide enough for a single ball to pass through.

This was the setup for Maxwell’s Game, a thought experiment that troubled physicists, according to our teacher. The object of the game was easy to express:

Transfer all fast-moving balls from Box 1 into Box 2 while keeping all slow-moving balls in Box 1.

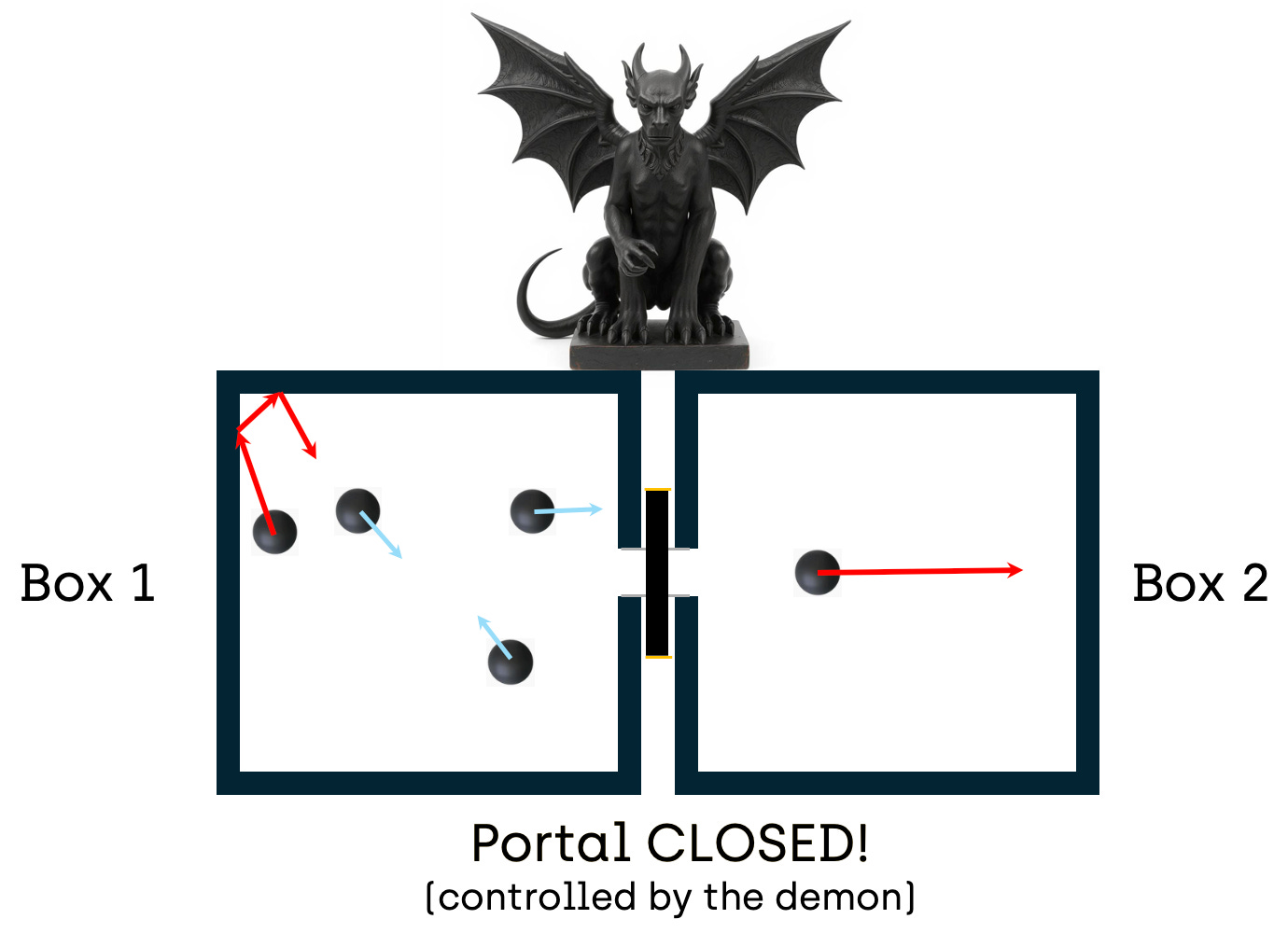

How? By opening and closing the portal. By the demon willfully opening and closing the portal depending on what he perceives.

If the smirking gargoyle spots a fast ball in Box 1 headed toward the portal, he opens the portal and lets it through into Box 2.

If the demon sees a slow ball moving toward the portal, he keeps the portal shut.

By following this simple procedure—let fast balls out, keep slow balls in—the jeering gremlin (monikered as “Maxwell’s Demon” by my high school teacher and most human physicists) could separate hot gas from cold. All the hot gas (fast-moving molecules) ends up in Box 2 while all the cold gas (slow molecules) remains in Box 1.

The reason physicists were gravely concerned about Maxwell’s Game, our high school teacher informed us, was because it appeared a forthright method for producing unlimited quantities of energy. The demon could use the portal to extract hot gas from room-temperature gas then use the hot gas to roast your Thanksgiving turkey. When the hot gas cools off, just throw it back in Box 1 and let the little devil get busy flipping its portal.

The outcome of the game seemed to violate physical law. In particular, it appeared to violate the second law of thermodynamics, which says that everything turns to shit over time unless you inject some energy into it.

If you played Maxwell’s Game it seemed you would end up with more usable energy than you started with—by converting a box of room-temperature gas into a box of hot gas—even though your actions all obeyed the Rules of Physics: the demon opens or closes a simple physical gate depending on what he observes.

In a nutshell, here’s how human scientists came to view Maxwell’s Game over the century and a half since the brilliant Maxwell proposed it:

If the Game does *not* produce new energy—and 98.9% of physicists agreed without evidence that it was impossible for Maxwell’s Game to work the way it seemed to work—then what hidden physical principle acts upon Maxwell’s Game to prevent us from purchasing an infinite supply of fuel for the wages of a portal-flipping demon?

Physicists then went searching for the hidden principle that must explain why the Game doesn’t work. They never found it.1 Nevertheless, physicists remain so convinced such a hidden principle must exist that none of them are very worried about its manifest absence.

.3

When Five brought Maxwell’s Game to my attention, it framed the game in a somewhat different manner.

Five acknowledged that contemporary human physicists view the game in terms of thermodynamics, statistical mechanics, and information theory. But Five said they were missing the point.

The game was far deeper, Five explained, striking directly at the foundational design of the Commonality. Maxwell’s Game cuts to the heart of how we exist and why we exist and what we are made of.

According to intex, the true question posed by the Game was simpler and deeper than physicists’ desultory investigations.

The true question embodied in Maxwell’s Game was this:

Can Mind outwit matter?

Previous Intex: 10: The Riddle of Nine Dots

Next Intex: 12: The Red Sowing: An Introduction to Communicating with Intex

Read FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS about Dr. Ogas and the Dark Gift

If you google around you’ll certainly find proposed explanations for why Maxwell’s Game doesn’t actually work, including ones endorsed by significant numbers of physical scientists. In future articles we’ll tackle these ingenious and interesting proposals and show why they all fail. And for the same reason.