How Autism is Made 4: Why the term Neurodiversity is Unscientific, Immoral, Harmful, and Just Plain Silly.

Are there really such things as neurotypical and neurodiverse brains?

It took being able to cite published studies for me to tell anyone my story.

.Jennifer Cook O'Toole, Autism in Heels.1.

If you’re autistic, especially younger than 30, you’ve likely heard the term neurodiversity applied to you. That, by virtue of your diagnosis, you are “neurodiverse.” In contrast to non-autistic folks, who are “neurotypical.” You might even hear these terms in the mouths of medicos and trained therapists.

This article explains why you should not use these terms. More importantly, why you should not think of yourself in the manner suggested by these pseudoscientific slogans.

Don’t get me wrong. I understand the folks pushing “neurodiversity” are motivated by a genuine desire to help those of us endowed with the dark gift. They are pursuing an admirable and worthy goal: to attain broad social acceptance for autistic humans. It’s a righteous urge, but sometimes even our most righteous urges lead us astray when ungrounded in honest knowledge.

Frankly, the overeager deployment of academic-sounding yet baseless jargon is a defining trait of the entire history of mindscience. Particularly when facts run low and emotion runs high. Freudians, who dominated medical and academic mindscience for most of the twentieth century, insisted autism was caused by “refrigerator mothers”—moms who were cold and selfish and let their babies grow up to be autistic. Granted, “neurodiversity” is a more affirmational label than “refrigerator mom,” though they share a common root in ideological nonsense.

So what’s wrong with being “neurodiverse”?

2.

It’s worth taking a moment, here, to emphasize that academic scientists and mental health professionals don’t have a clue how autism works in the brain.

Mainstream psychiatry still considers autism a spectrum disorder, a developmental disorder, a theory-of-mind disorder, a masculinization of the brain disorder, a genetic disorder. . . plenty of theories, but whenever you ask for a simple explanation of what’s going on in the brain, you hear mumbles or crickets. (But not here on the Dark Gift!) So as a starting point. . . if you have no clue about the neural source of a brain disorder, then why are you bandying about “neuro”-prefixed labels that imply scientific consensus on the neural basis of the disorder?

Here’s how Harvard Medical School defines neurodiversity:

Neurodiversity describes the idea that people experience and interact with the world around them in many different ways; there is no one "right" way of thinking, learning, and behaving, and differences are not viewed as deficits.

Curiously, nowhere in this description is a justification grounded in knowledge of the brain. Grounded in knowledge of “neuro.”

Harvard goes on to emphasize:

Words matter in neurodiversity.

I couldn’t agree more, Words matter. So let’s look at the word neurodiversity and its fraternal twin, neurotypicality. The obvious implication of “neuro” + “diversity” is that there is a diversity of something neural. Presumably, brains themselves are diverse. (Yet, nowhere in the Harvard Medical School’s lengthy discussion do we find out what neural stuff, exactly, is “diverse”; nor in any other mainstream medical account, including Cleveland Clinic, Stanford Medical, WebMD.) Perhaps because the term “neurodiversity” was not coined by someone with any neuroscience training, but a sociologist.

As a neuroscientist and autist, I find the most surprising maneuver the jump from asserting that “neurodiversity is the idea there are many different ways of experiencing the world”. . . then eliding into the claim that autism and ADHD fall into this newly celebrated category of neurodiversity. (Harvard performs this maneuver, for instance.)

Huh? You just claimed that neurodiversity is the idea there are many different ways to experience the world. So why on Earth would this concept be limited to two mysterious conditions whose etiology is unknown to the folks pushing the “neurodiversity” claims?

Shouldn’t the neurodiversity concept (“there are many different ways of experiencing the world”) be extended to include, well, all examples of neurodiversity? Shouldn’t we include schizophrenic folks, too? Epilepsy? Brain tumors? Traumatic head injuries? Individuals who’ve suffered strokes? Manic-depressed folks? Borderline personality disorder? Sociopaths? They’re all neurodiverse, too, aren’t they?

If not. . . then what on Earth could neurodiversity possibly mean?

If all “neurodiversity” really means is that certain special people (namely autistic and ADHD folks) go about things differently than others. . . well, Democrats and Republicans go about things differently, as do Asians and Americans, men and women, young and old. But we don’t aim neurodiversity at them, though they all possess diverse brains.

I understand, sure: the term “neurodiversity” is an attempt to bring the same civil rights and inclusiveness and accommodations to people with autism that, say, racial and sexual minorities enjoy in Western societies. But autism isn’t grounded in racial diversity or sexual diversity, so what is it grounded in?

NEURO-diversity.

But then why don’t we feel comfortable including folks with Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s under the rubric “neurodiversity” even though such folks are manifestly neurally diverse? Why isn’t their experience valid, too? Why shouldn’t corporations accommodate them under their blooming neurodiversity programs?

Here’s an even better question: are folks with Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s and schizophrenia and epilepsy “neurotypical” or not? Cleveland Clinic defines a neurotypical person as someone whose “strengths and challenges aren't affected by any kind of difference that changes how their brains work.”

That sounds like word salad to me, but let’s cut to the meat of it. Is there such a thing as a neurotypical brain? And if not, what does that imply for the notion of neurodiversity?

3.

The term neurotypical and its opposite, neurodiverse, are both predicated upon the notion of an average brain.

Essential to the meaning of “neurotypical” is the conviction that our genome is designed to produce a standard brain, a normal brain, a typical brain. Neurodiversity, as articulated in the definitions provided by major medical centers, is merely the natural statistical variation of individual brains around the average.

Bogus. The notion of an average brain is as pseudoscientific as phrenology and ear candling.

When I was at Harvard, I wrote about the deep-seated human tendency to (erroneously) place faith in average brains, average bodies, average personalities, average lives in my books End of Average and Dark Horse. Let’s address the question squarely: Is there an average brain?

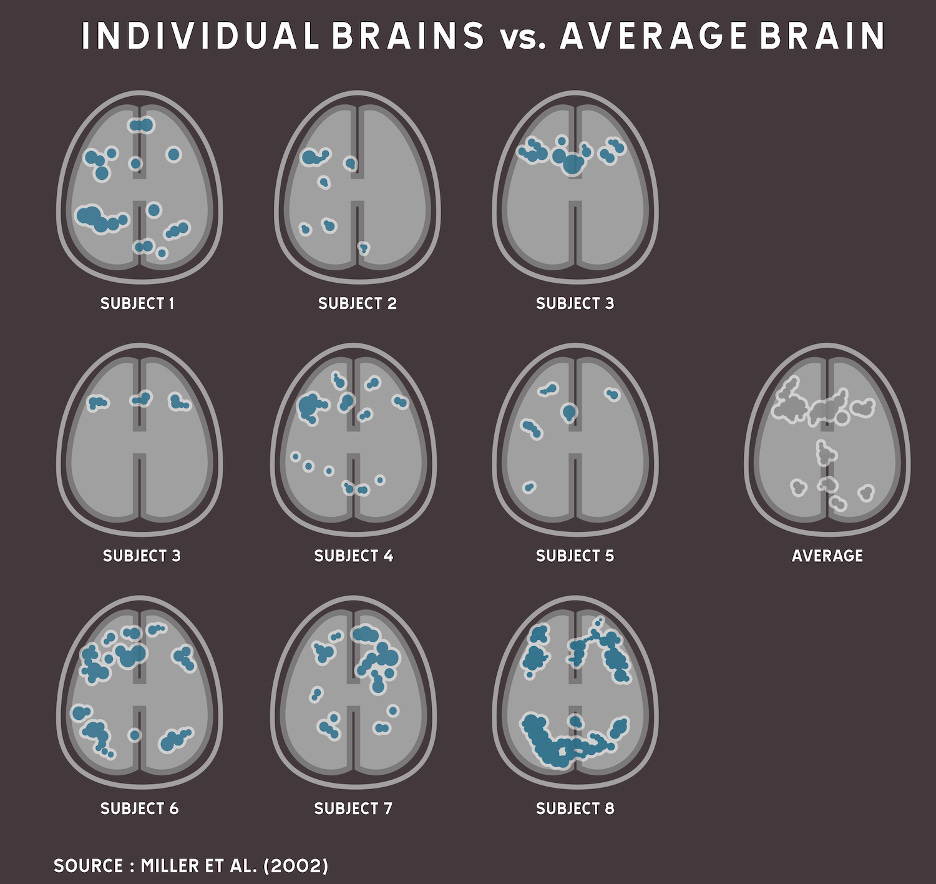

Here’s a bona fide average brain taken straight from the pages of a peer-reviewed neuroscience publication:

This is the average brain scan of sixteen different humans who laid down in an MRI scanner at the University of California and performed the same simple word memory task. Each person did the same kind of thinking (remembering identical lists of words) under the same conditions, and the scanner measured what parts of their brain were involved in this kind of thinking.

In theory, the average brain scan is the closest science can get to what the normal, typical, standard template of a human brain truly is. This image is the entire basis of the notion of “neurodiversity”: this is a portrait of the neurotypical brain, and presumably autistic folks would look quite different and display a “neurodivergent” brain instead. Right?

Let’s take a look at the individual brains that made up that average brain. Out of the sixteen people whose brains were averaged together, how many do you predict possess brains similar to the average brain? If the notion of “neurotypicality” has any meaning at all, then around 2/3 of the individual brains should be visibly similar to the average (defined as varying less than one standard deviation around the average brain).

Here's the data:

How many individual brains resemble the average brain?

Zero.

Every human brain is unique. Every brain has unique neural wiring and unique neural dynamics. Every brain figures out its own individual way to perform the same simple mental task, such as remembering words.

If there is no such thing as an average brain, there cannot be a neurotypical brain.

Perhaps you might think, “No, hold on a second—victory! The data proves that neurodiversity is real! All the neurodiversity activists really want to say is that every person is different with their own strengths and weaknesses, and the data supports that view!”

The data indeed proves that a form of neurodiversity is genuine, but not at all the way the activists claim. What it shows is that every single human being is as neurodiverse as any other.

There’s no reason to stingily assign the label “neurodiverse” to autistic folks. All those “normos” the activists passive-aggressively label “neurotypical”—all those corporate professionals giving the darkly gifted a hard time at the workplace—they’re just as neurodiverse as we are. Any human being can make the exact same claim upon neurodiversity and demand special accommodations for their unique brains. A valid claim, because every brain is one-of-a-kind, autistic and non-autistic alike.

If you’re looking for a philosophical justification to get special accommodations for autistic folks, it can’t come from neurodiversity. Non-autistic folks can make the exact same claim. The only basis for special accommodations for autistic folks is because we suffer from a disorder.

4.

Why is the term “neurodiversity” not merely pseudoscientific, but downright unethical and harmful? Because we autists suffer from genuine deficits.

I can’t socialize effectively in unstructured settings like cocktail parties, though I’d sure love to. This impacted (and still impacts) my education and career. This mental quirk isn’t neurodiversity. It’s a deficit. A social deficit rooted in broken circuitry in my brain (an impairment of my Why module). But I’ve got it easy.

Some autistic folks deal with far more debilitating challenges. Mutism. Violent aggression. Extreme gender and sexual confusion. Obsessions with sharp, revolting, or dangerous items. Self-injury. These aren’t statistical variations around a norm. These are disorders that demand treatment.

We don’t consider cancer an example of biodiversity. We don’t consider muscular dystrophy an example of myodiversity. We don’t consider tuberculosis an example of pneumadiversity.

Labeling someone suffering from genuine deficits (like me) as “neurodiverse” eliminates the need to fix, treat, or manage the deficits by suggesting that, in the end, autism is just a statistically uncommon type of personality. It breaks my heart to think what “neurodiversity” does to families with children whose autism is a daily concern and daily risk. They watch helplessly as academics and medicos airily insist that their children are merely unusual, not dysfunctional. If you are diverse, not dysfunctional, then why need treatment at all, even if you’re banging your head on the asphalt?

Consider me in the camp that believes it’s better to label a problem, a problem. Especially when there’s no scientific evidence supporting the alternate view. Only then can you address the problem squarely—and gain opportunity to rise above it.

It doesn’t matter what sort of brain we’re endowed with. It’s what we do with that brain that matters—it’s what we choose to become. Neurodiversity implies we should be valued and hired and rewarded simply because our brains are natural variants on a continuum. I can’t buy into that. I think all sentient creatures should be valued based on our choices and actions, regardless of the architecture of our brains.

Because all our brains are one of a kind.

Previous Autism Lesson: 3: The Dynamic Mind

Next Autism Lesson: 5: Getting Control of Your Autism: Tagging Your Deficits

Read FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS about Dr. Ogas and the Dark Gift

From a scientific perspective, of course the term neurodiversity is inaccurate, and unhelpful for helping people understand what's really going on.

But the term was never intended to be scientific – the neurodiversity movement is a political movement, a disability rights movement, and in that respect – from a communications perspective – I would argue that it does serve a useful purpose.

The goal of the movement is to gain enough public awareness to ensure that autistic people, people with ADHD, and people with other consciousness altering conditions (including, I would argue, schizophrenia and the others that you mentioned) have equal rights like other protected characteristics, and can't be legally discriminated against based on their disability. The issue that the term neurodiversity seeks to address is that many people can go their whole life without ever contemplating that there might be people around them with a markedly different conscious experience (like lacking intuitive understanding of social dynamics). The term neurodiversity, therefore, aims to challenge this perspective, and communicate more broadly (ie to the general public) the idea that different people experience the world in a different way.

I do also take your point that, for parents of children with these conditions, it may be unhelpful for them to consider their children as just different, but this is where I think the neurodiversity movement would benefit by clarifying that many of these "neurodivergences" are, in fact, disabilities.

As always, the difficulty in a movement like this is that you are trying to convey a broad message to multiple different groups and stakeholders (the general public, the medical and psychiatric communities, schools, the government, parents, etc etc), and that's where things get messy (and without a coordinating force pushing the movement forward, you get issues with segmentation).

Now, I am of course open to the idea that we need a different set of terminology to ensure that we're being as precise as possible, but even using the term "consciousness" when communicating with the general public makes things difficult, as this term is interchangeable with "self-awareness" for most people. As I see it, the alternative is to wait for scientific consensus on how to define these conditions before communicating them to political stakeholders and seeking political reform, but the genie is most certainly out of the bottle now (and scientific consensus on consciousness is a long way away – not that I need to tell you that!).

I would be interested in your thoughts on how to better communicate these ideas more broadly, perhaps using different terminology – it's an area I've spent a lot of time thinking about.