... if you want to contact intex, is it better to use physics or mindscience?

Conundrum Four: Part I: The First Physicists Become World-Mongers

In the earliest recorded debates about intex, the world-mongers were drawn from ancient mindscientists and the one-worlders arose from ancient physicists. But a thousand and a half years later, physicists experienced a wholesale religious conversion to world-mongering.

Physical scientists’ abandonment of their long commitment to geocentric monotheism coincided with the emergence of astronomy as the first modern scientific discipline in the sixteenth century. It was the newborn astrophysicists, theoreticians of the freshly rearranged cosmos, who led the great pivot from wholesale rejection of intex to an enthusiastic embrace of infinitely peopled worlds.

Copernicus (1473–1543) is usually considered the midwife of la science moderne, with his subversive heliocentrism—We are not the center of Creation!—yet, perhaps because of the mutinous audacity of his theory, the Polish stargazer never made any public comment, yay or nay, regarding life on other orbs.

Tyco Brahe (1546-1601) of the golden nose[1] was perhaps the last card-carrying one-world physicist (or at least, one-solar-system), mainly because he rejected the Copernican idea of colossal space, which he viewed as an unnecessary and unlikely waste, following similar reasoning as ancient advocates of the One World Doctrine.

Pioneering cosmologist Giordano Bruno (1548–1600), a supremely self-confident poet and occultist, may have been the prime instigator of the great renaissance in world-mongering. He penned De l'infinito, universo et mondi (On the Infinite, Universe and Worlds, 1584), where he imagined, in exuberant detail, the inhabitants of the planets and stars and attributed a purposeful soul to the cosmos.

Bruno’s views greatly stressed Johannes Kepler (1571–1630), who rejected the idea of a universe with endless inhabited worlds. Kepler was willing to accept the possibility of life on the moon or known planets: he wrote Somnium, a fictional voyage to an inhabited moon, and separately proposed that the most likely home for intex in our solar system was Jupiter, because its four moons were “not for us” but instead served “the occupants” of the largest planet. Nevertheless, the idea that the universe vouchsafed neverending worlds was anathema to Kepler, because he nursed deep faith that God designed the universe for man.

Kepler lived in fear that his ambitious stargazing contemporary Galileo (1564-1642) would find evidence of life outside the solar system. Upon reading the Italian’s Sidereal Messenger, Kepler wrote to Galileo to express his relief that Galileo failed to find evidence of a single extrasolar planet (which Kepler assumed would be inhabited).

Galileo himself, perhaps for diplomatic reasons, publicly offered a cautious, somewhat agnostic perspective on world-mongering, writing in “Letter on Sunspots”:

I agree with Apelles in regarding as false and damnable the view of those who would put inhabitants on Jupiter, Venus, Saturn, and the moon, meaning by “inhabitants” animals like ours, and men in particular. Moreover, I think I can prove this. If we could believe with any probability that there were living beings and vegetables on the moon or any planet, different not only from terrestrial ones but remote from our wildest imaginings, I should for my part neither affirm nor deny it, but should leave the decision to wiser men than I.

But a little more than a century later, in the second half of the 1700s, those scientists scrutinizing the shape and fate of the cosmos were almost exclusively committed to world-mongering. In 1750, Thomas Wright of Durham (1711-1786), son of a carpenter, wrote Original Theory of the Universe, a tract in which he “set for himself the colossal task not simply of constructing a new conception of the physical cosmos but also of integrating into it the domain of the spiritual.” The book contained a chart that delineated the positions of an inexhaustible number of worlds[2] arranged around a center which held a “Sacred Throne of Omnipotence.” Wright described it thus:

Suns crowding upon Suns, to our weak Sense, indefinitely distant from each other; and Miriads of Miriads of Mansions, like our own, peopling Infinity, all subject to the same Creator’s Will; a Universe of Worlds, all deck’d with Mountains, Lakes, and Seas, Herbs, Animals, and Rivers, Rocks, Caves, and Trees; and all the Produce of indulgent Wisdom, to chear Infinity with endless Beings, to whom his Omnipotence may give a variegated eternal Life.

Wright even drafted an illustration of the infinite cosmos depicting the sections of shells of stars, each star having at its center the “Eye of Providence,” reminiscent of the Salvador Dali dream sequence in Hitchcock’s Spellbound:

Wright’s vision of infinite eyes inspired the towering rationalist philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) to embrace world-mongering. In 1755, Kant wrote in his Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens, “the cosmic space will be enlivened with worlds without number and without end.” According to Kant, this process of enlivening takes place over time, with the very first worlds being formed near the chaotic “center” of Kant’s infinite cosmos, with chaos gradually giving way to order in the more remote regions. Kant suggests that the denizens of the central worlds are of low intelligence and character, whereas “the most perfect classes of rational beings [are] farther from that center than near it.” This imputed hierarchy of beings forms a great chain of rational minds for Kant in which these minds progress through “all infinity of time and space with degrees, growing into infinity, of perfection of the ability of thinking, and bring themselves gradually closer to the goal of the highest excellence, namely, to divinity. . . .”

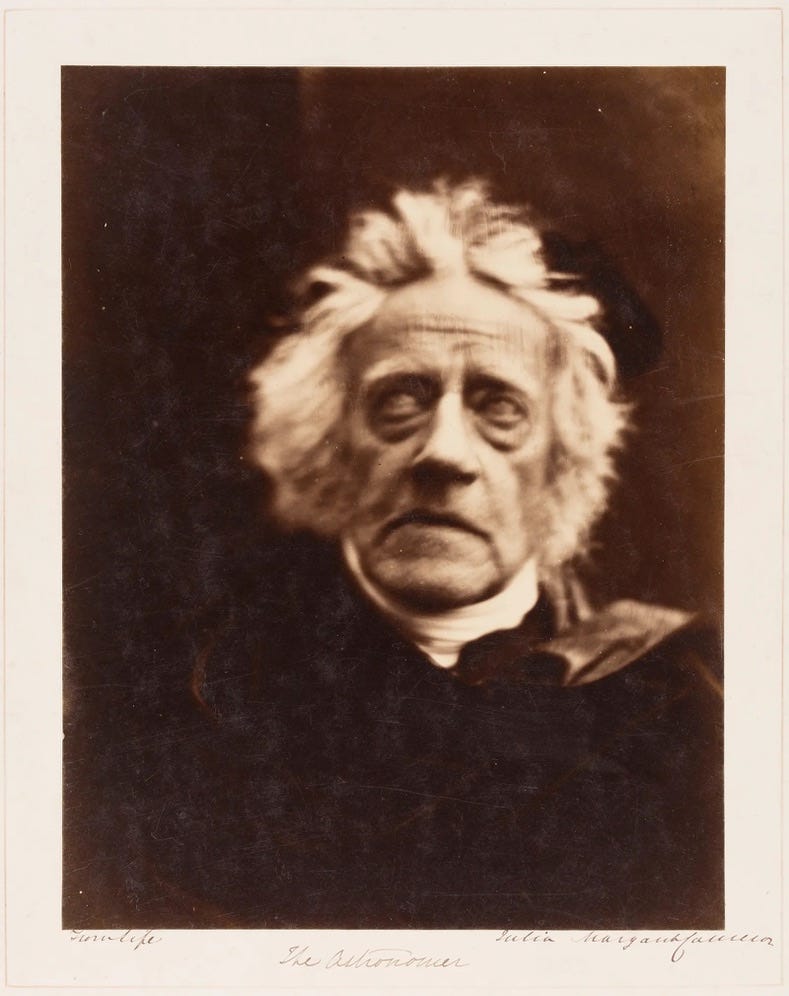

The greatest astronomer of the era was undoubtedly the British observer William Herschel (1738-1822). He is most famous as the discoverer of Uranus, but in a paper he submitted in 1780 Herschel proclaimed he was on the verge of a far more momentous discovery:

the knowledge of the construction of the Moon leads us insensibly to several consequences . . . such as the great probability, not to say almost absolute certainty, of her being inhabited. . . who can say that it is not extremely probable, nay beyond doubt, that there must be inhabitants on the Moon of some kind or other? Moreover it is perhaps not altogether so certain that the moon is out of the reach of observation in this respect. I hope, and am convinced, that some time or other very evident signs of life will be discovered on the moon. . . . For my part, were I to chuse between the Earth and Moon I should not hesitate to fix upon the moon for my habitation.

In fact, Herschel’s profession of his faith in intex, though open-hearted and alacritous, nevertheless understated his true convictions: Herschel secretly believed that he had already discovered life on the moon. In a 1776 journal of his lunar observations, Herschel recorded:

I believed to perceive something which I immediately took to be growing substances. I will not call them Trees as from their size they can hardly come under that denomination, or if I do, it must be understood in that extended signification so as to take in any size how great soever. . . . My attention was chiefly directed to Mare humorum, and this I now believe to be a forest, this word being also taken in its proper extended signification as consisting of such large growing substances.

Herschel was pummeled with push-back from the scientific community, who accused him of being unscientifically bold. He grew wary of being perceived “fit for bedlam” and “declared a Lunatic” and learned to keep his intex obsession secret, or at the very least, out of the papers he submitted for publication.

Herschel’s fears of being fit for Bedlam were well-founded. In 1787, a man named Dr. Eliot went on trial for insanity, and one of the items admitted into evidence in support of this claim was the fact he had submitted a paper to the Royal Society in which he asserted the sun was inhabited[3]. Nevertheless, though Herschel became restrained in his public pronouncements about life on other worlds, in private he never stopped pursuing intex. He cajoled King George III into granting him the princely sum of 4,000 pounds to build the largest telescope on Earth—not to discover new nebulae or other astronomical structures, but to discover intex.

There is no evidence that he did.

[1] In 2010, gravediggers exhumed Brahe’s withered corpse in a moment of blasphemous curiosity to determine the true substance of the Dane’s prosthetic beak and discovered it was not gold, as long rumored, but brass.

[2] Though he calculated only 170 million inhabited worlds existed within “our finite view.”

[3] Eight years later, Herschel agreed with this very claim.

Previous Intex: 3 … can you determine *WHEN* intex exist by sitting alone in your room contemplating time and chance?

Next Intex: 5 . . . if you want to contact intex, is it better to use physics or mindscience? Part II